Some movie monsters have become so ubiquitous in popular culture that they feel more like omnipresent myths than characters from specific stories. Ask any young child and they’ll probably recognize Frankenstein and Dracula without ever having touched a Stoker or Shelley novel, with these characters inhabiting our collective imagination through what can only be described as cultural osmosis. This natural process obviously goes against the corporate interests of studios like Universal, and that’s why the company continues to invest millions of dollars into licensing deals in order to keep their monster movies in the spotlight as the “definitive” versions of these stories.

While it’s only fair that creators should get to monetize their hard work, corporations turning creativity into a business has resulted in a media landscape that favors brands instead of ideas. I was recently reminded of this weaponization of intellectual property when I watched the trailer for Paul Dudbridge’s Fear the Invisible Man, a low-budget rendition of H.G. Wells’ classic story that many internet commenters were unfairly likening to a mockbuster when compared to the recent Invisible Man remake.

And in a world where modern bogeymen are copyrighted and virally marketed instead of being shared organically like they used to be, I think this might be a good time to discuss the importance of public domain monster movies like Dudbridge’s passionate little adaptation. After all, not everything has to be part of an interconnected franchise – and multiple versions of the same ideas can be a good thing if they’re coming from unique voices.

The precise definition of public domain varies from country to country, but these days it’s mostly accepted that the term refers to a collection of creative work that no longer belongs to any specific person or company. While ancient Rome already had laws protecting certain universal concepts from ownership, modern copyright has its roots in the invention of the printing press, with early publishers wanting to keep rivals from simply reprinting existing books. This legal oversight eventually led to creators being able to secure a living from their work, something that continues today in several mediums.

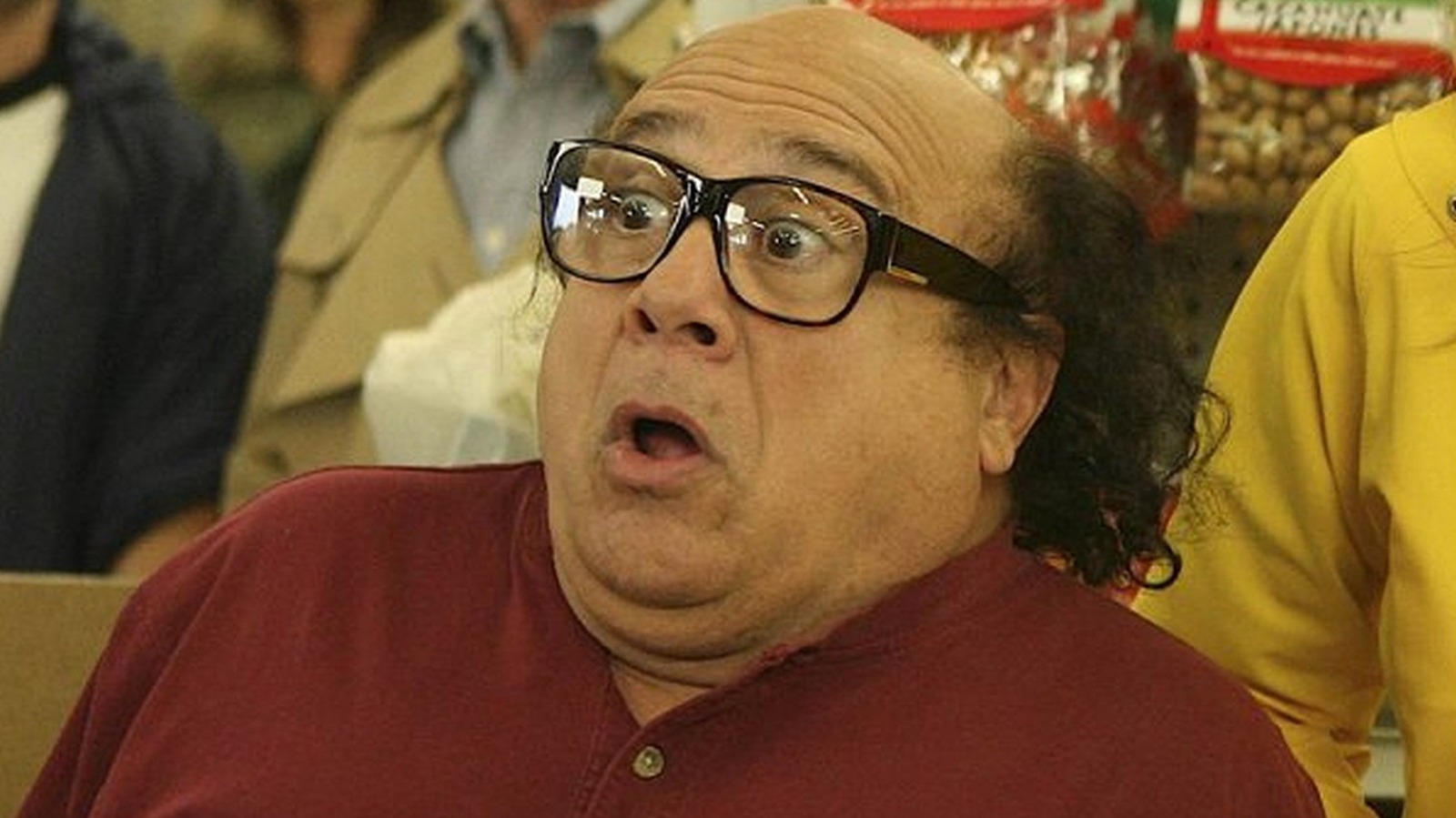

When it comes to monsters, the more the merrier!

But what does this have to do with monster movies? Well, humankind has been sharing horror stories since time immemorial, and these stories and their respective monsters change as they’re retold by different artists. Go back far enough and werewolves and vampires have their roots in the same flesh-eating creatures, and we’re likely to spawn even stranger legends a few centuries from now. This constant evolution is a huge part of what makes horror so appealing in the first place (like how zombies have been resignified to represent everything from capitalism to fear of disease over the years), but an unhealthy prejudice against public domain scares can get in the way of that.

I mean, if it wasn’t for Night of the Living Dead accidentally entering the public domain, zombie movies would probably have become a Romero-specific specialty instead of an all-out genre. If you think about it, there’s no telling how many potential classics we’ve been robbed of because of pesky copyright laws. While Jason Voorhees is still limited by legal complications, older characters like Dracula are still going strong even after being portrayed by a hundred different actors over the course of a century (with impressive fan-films like Never Hike Alone further suggesting that big studios aren’t the only ones that can do these characters justice).

I’m obviously not about to suggest that horror filmmakers descend into anarchy and start ignoring copyright laws altogether (though it’s worth remembering that one of the most faithful adaptations of Dracula was made without the author’s consent), but I think it’s worth celebrating when lesser-known artists can tackle the same material as big studios in unique and creative ways.

After all, these shared narratives also serve to fuel the next generation of horror by giving up-and-coming storytellers a solid base to borrow from without fear of repercussion. We wouldn’t have the Hulk without The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, and Frankenstein was already in the public domain by the time James Whale brought the story to the big screen back in 1931.

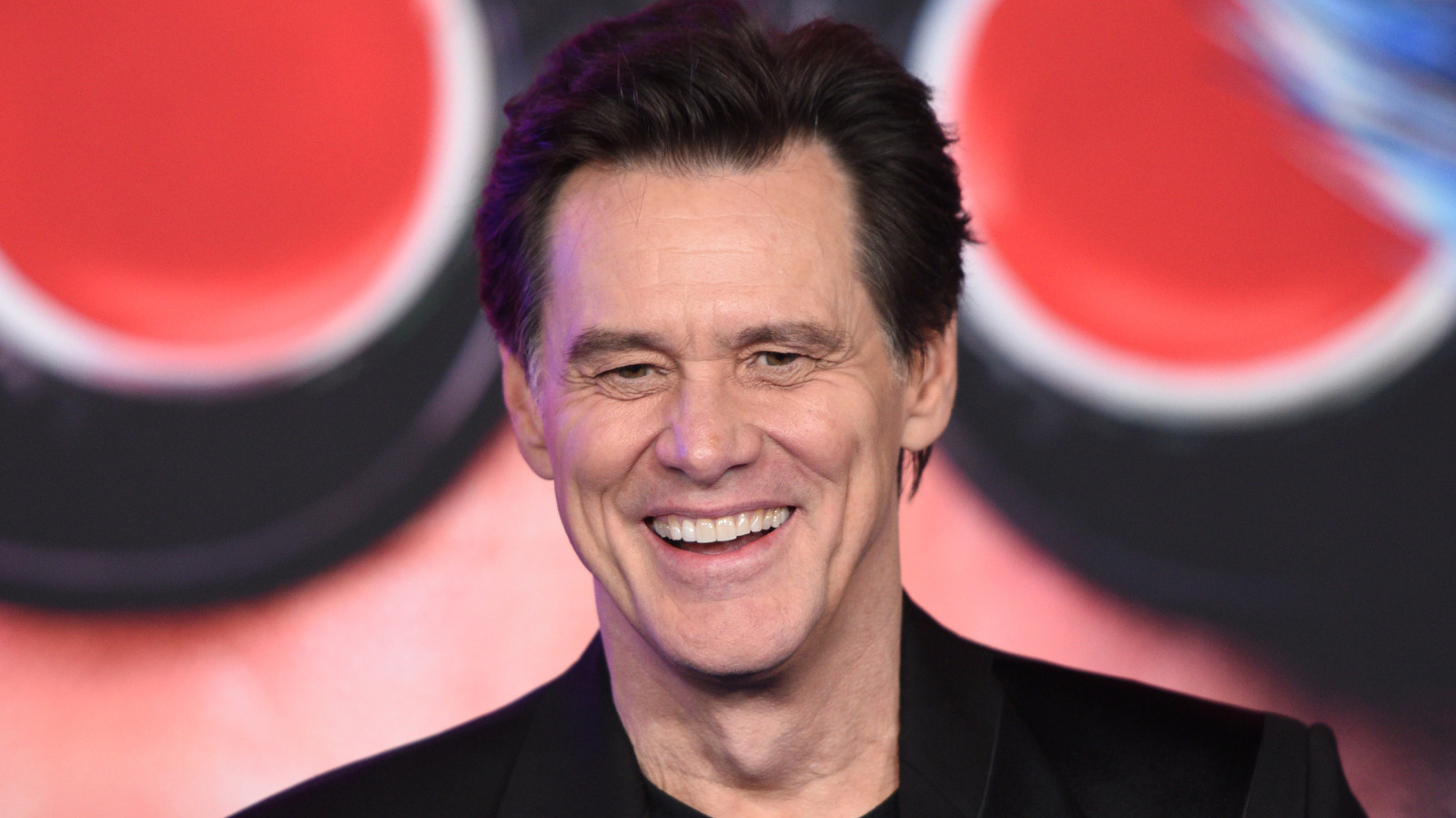

Does the existence of Nosferatu make Dracula any less iconic?

While the natural lifecycle of these creations has been unnaturally extended by companies like Disney (who continue to bargain for longer copyright terms), even Universal’s iconic monsters are set to enter the public domain alongside their source material during the next decade or so. With that in mind, maybe it’s time for horror fans to embrace off-brand monsters instead of searching for a definitive version.

If Guillermo del Toro can win an Academy Award for his off-brand take on The Creature from the Black Lagoon, then I think it’s okay for indie filmmakers to come up with their own interpretations of these classic monsters without fear of being rejected by the horror community simply because they don’t fit in with the established “canon.”

At the end of the day, Dudbridge’s Fear the Invisible Man is by no means a masterpiece, lacking the pathos of the original story and the carefully crafted thrills of the more recent iteration, but I’m glad that this strange little project can co-exist with its big-budget cousin if only to remind audiences that H.G. Well’s iconic creation belongs to everyone – not just Universal Studios. Hell, if it were up to me, we’d be seeing generic Invisible Man spin-offs harkening back to Universal’s original set of comedy and spy thriller sequels from the 1940s.

Companies will always worry about genericization leading to a loss of brand identity, but it’s exactly this freedom that allows a monster movie (or any other kind of media, for that matter) to become a bona fide legend. And as a lifelong horror fan, I can’t wait to see what kind of fresh terrors the next generation of storytellers will come up with next if they’re allowed to reuse and iterate on what came before.

Fear the Invisible Man is available now on VOD outlets.

:quality(85):upscale()/2026/02/11/999/n/1922564/19ffb493698d09b779a029.93496973_.png)

:quality(85):upscale()/2026/02/10/005/n/1922564/85a2b8ad698bba41400309.88193761_.jpg)