On the surface, David Cronenberg’s 1996 adaptation of J.G. Ballard’s 1973 novel Crash is a drama about an unlikely group of people who come together over their shared fascination with car crashes.

The novel is written in the first person from the point of view of Ballard’s proxy, James Ballard. He’s a successful film producer in an open marriage to wife Catherine; both partners routinely engage in casual sex with co-workers and strangers alike, seemingly in pursuit of upending their relationship ennui.

The sex, which is captured by Ballard in incredibly specific and laborious prose, is cold, dispassionate, and almost clinical. The novel is often described as a work of science-fiction; despite containing virtually none of the tropes of the genre, Crash reads like a warning of a dystopian future in which citizens have become so desensitized that they will be pushed to pursue more and more extreme outlets in order to feel something.

That something, as both readers and viewers of the film will know, is car crashes.

Considering how confronting and racy the book is, the David Cronenberg film adaptation of Crash is something of a marvel. Ballard’s book was long thought impossible to adapt and the movie, which features lines of dialogue lifted straight from the novel, as well as copious amounts of sex and nudity (much of it fetishistic and queer) is provocative, confronting and even a little dangerous. In case the divisive nature of the movie isn’t clear, when it debuted at Cannes, Crash provoked both walk-outs, as well as a special Jury prize for its audacity.

James Spader stars as James Ballard in the film version, while Deborah Kara Unger plays his wife Catherine. The film opens with both engaging in extra marital affairs (his at work on set, hers at an airplane hangar – a carry-over from her flight lessons in the book). That night on the open terrace of their luxury Toronto high rise, they take turns talking about their trysts in order to stimulate each other. Their oft-repeated line “Maybe next time” is verbal evidence of a disaffected sex life and lack of connection to one another.

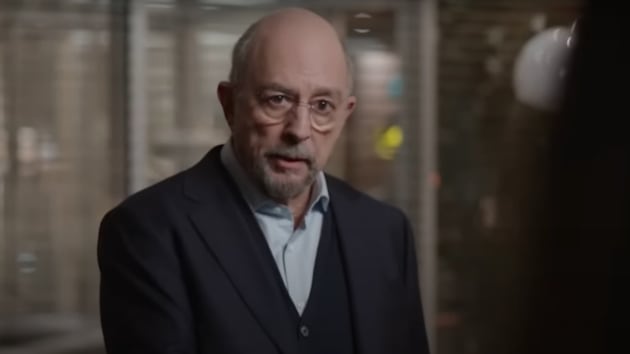

Things change when James distractedly causes a head-on collision that kills another man. Not only does this event shift him into the orbit of the dead man’s wife, Dr Helen Remington (Holly Hunter), but it puts him on the radar of badly scarred car crash enthusiast Vaughan (Elias Koteas).

While the film definitely focuses principally on character (and sex)-driven sequences, under closer consideration, it’s clear that Vaughan is something of a cult leader. He has amassed a collective of acolytes who hang on his every word; these are individuals who have become so enamored by his obsession that they effectively abandon their own lives in order to sleep with each other and study Vaughan’s archival collection of car wrecks.

In the clearest evidence of Vaughan’s cult of personality, his dear “friend” Seagrave (Peter MacNeil), whom Vaughan encourages to drive in simulations despite successive concussions, eventually dies in a manufactured recreation of Jayne Mansfield’s death. In the virtuoso sequences, Ballard, Catherine and Vaughan survey the massive traffic jam and the plethora of injuries caused by Seagrave’s crash, but Vaughan’s only response upon seeing his friend’s body is bemoaning the fact that Seagrave didn’t wait for him. This is a man unafraid to embolden his followers to commit acts of violence, who can’t even feign sadness at their passing when they inevitably perish in the resulting destruction.

Throughout the film, Vaughan is clearly a dark shadow figure lurking over the narrative. He exhibits classic stalker behaviour: disguising his identity in order to conduct surveys and take pictures of crash survivors like Helen and Ballard. He also voyeuristically photographs them (and others) having sex, and he frequently tails them in his giant black car.

Not unlike a horror villain’s tool of choice, the car acts as both an extension of Vaughan, as well as a weapon with which to terrorize and pursue his victims. As the film progresses and the relationships begin to intensify, Vaughan appears to lose interest in his former crew so that he can focus on Ballard and Catherine, whom he repeatedly engages with via vehicular contact, as well as sexual dominance.

Vaughan frequently chases the couple with his car, particularly Catherine, who is the final member of the ensemble who has not been in an accident. Not unlike a slasher villain, Vaughan stalks his prey, hanging back in his car to draw out the chase before jerking forward and startling, or even rear ending, them. The relationship between the cars’ physical contact and human appendages isn’t difficult to discern: like a car-obsessed version of Jigsaw, Vaughan figuratively and literally rams into Ballard and Catherine with his oversized appendage in order to make the couple feel something, to make them feel alive.

This idea comes full circle at film’s end. After repeatedly trying to indoctrinate Ballard and Catherine into his group, Vaughan makes one final (suicidal) attempt, his car flying over the guard rails and crashing into a bus on the freeway below. Not only does his end reinforce the film’s nihilistic interest in equating car crashes with sexual intercourse and death, Vaughan’s passing effectively promotes Ballard to become his successor.

In the film’s final moments, Ballard literally replicates Vaughan’s actions, chasing down his wife in his own oversized car and instigating a car accident before initiating sex with her on the side of the road. The fact that they repeat the same line of dialogue from the start of the film (“Maybe next time”), suggests that the crash wasn’t entirely successful in reigniting their relationship and that they will continue to rely on Vaughan’s habit of using of car crashes to incite interpersonal connectivity.

Despite its lack of traditional genre conventions, David Cronenberg’s Crash absolutely contains elements of both slasher films and erotic thrillers. The intersection of sex and death, Vaughan’s ability to steer and manipulate the narrative, as well as how he uses his car like a weapon, all feel very horror inspired. Crash may be an unconventional example of the subgenre, but we should expect nothing less from a master like David Cronenberg.

Sex Crimes is a column that explores the legacy of erotic thrillers.

![Mason Ramsey – Twang [Official Music Video] Mason Ramsey – Twang [Official Music Video]](https://i.ytimg.com/vi/xwe8F_AhLY0/maxresdefault.jpg)