Why TerrorVision?

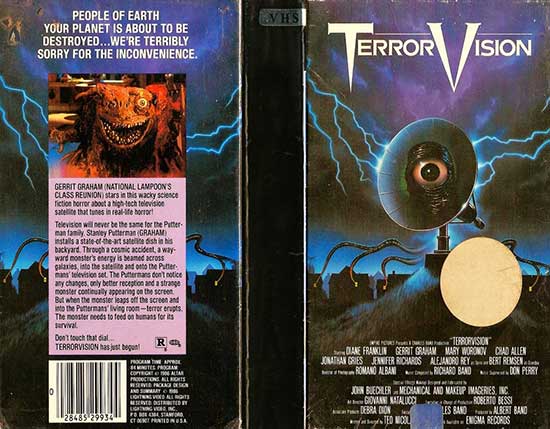

The 1986 Empire Pictures production caught my eye even after getting dogged by “dog” ratings. Poor reviews didn’t stop me from eventually checking out the old Lightning Video VHS tape one day in 1987 or 1988. The oddball film impressed few back then, but today the low-budget sci-fi/horror/comedy/travesty gets the occasional second look as an understated parody of 1980s culture.

That didn’t stop me from eventually checking out the old Lightning Video VHS tape one day in 1987 or 1988. The oddball film impressed few back then, but today the Z-grade sci-fi/horror/comedy/travesty gets the occasional second look as an understated parody of 1980s culture.

Understated? Maybe not.

The Empire Rises and Falls

Charles (Full Moon Features) Band ran Empire International Pictures, a company that saw both glory and collapse in the 1980s. Empire released several exceptional outings, such as Dolls (1986), Prison (1987), From Beyond (1986), and the landmark H.P. Lovecraft’s Re-Animator (1985). Weirdly but not unexpectedly, the company’s biggest hit was the lame Gremlins (1984) rip-off Ghoulies (1985), with the weak Troll (1986) also being a moneymaker.

Besides promoting theatrical releases, Empire Pictures flooded the growing VHS market with its product. An arrangement with Vestron/Lightning ensured decent distribution where a niche home video audience appreciated (or didn’t appreciate) the low-budget, sometimes poorly conceived B-grade films from the company’s development and production offices. Empire put much effort into several projects, hoping for another surprise hit. TerrorVision was one of those films.

Empire Pictures did well for a time. Like its action film house contemporary, Cannon, the company found itself struggling with costly projects in a challenging landscape. Films like TerrorVision received little or no theatrical distribution, and their home video sales didn’t save the company from losses.

Is TerrorVision a forgotten masterpiece awaiting rediscovery? No, it’s schlock. Still, the timepiece deserves a second look for its sly critique of 1980s pop culture weirdness.

Totally Awesome 80’s Pop Culture

The 1980s may have turned in a direction far different from the radical 1960s and the swinging 1970s, but the decade thrived on its outrageously consumer-driven oddness. TerrorVision mocks the rawness of that consumerism. Ineptly. And sincerely.

Synopsis: Dumping garbage into outer space is a bad idea, but turning trash into generic energy makes things less interstellar-messy. Converting a weird creature called Hungry Beast into energy gets him off the inhabitants of planet Pluton’s shoulders but inadvertently causes some woes for planet Earth.

Meanwhile, on the blue and green marble, the Putterman family’s home has a new satellite dish that inadvertently draws energy trash from outer space, shaking up their television viewing. The intergalactic energy soon pops out of the TV and returns to solid form. Hungry Beast soon runs amok in the suburban household.

He starts consuming obnoxious 1980s nuclear family members, “Start” is the key word. Hungry Beast won’t stop until he eats up the whole planet.

Can the rebellious Putterman siblings stop Hungry Beast?

TerrorVision continued Empire Pictures’ trend of producing a film with special effects that now look awful in 2023. (In 1986, the effects were merely terrible.) Seemingly, there doesn’t appear to be any underlying subtext with the cheap effects. A low budget means little money for elaborate effects, and a science-fiction-styled horror movie would strain the budget even further. The aliens, lightning, and rays shooting out of the television all look abysmal. No overarching comedic irony pushes the effects to look so poor. Budget limitations did.

TerrorVision’s cheap effects succeed in highlighting a satirical irony. The 1980s often delivered self-parody in the form of earnest seriousness. TerrorVision’s cheapness mimics real-life cultural vapidness. Maybe the hands of the 1980s gods guided the special effects.

Not so inadvertent is TerrorVision’s bludgeoning broad attack on materialism.

Material Girl, Guy, Family, & Space Alien

That surname. Putterman. Many traditional surnames come from conventional professions. Smith comes blacksmith. Taylor derives from tailor. Carpenter is self-explanatory. Putterman makes you think of someone with discretionary income frittering away time on a golf course.

The Puttermans, swinging mom and dad, Rambo grandpa, punk rock teen daughter, and generic annoying pre-teen son are the prototypical 1980s nuclear (sitcom) family. Mom and dad never got the memo that swinging was a thing in the 1970s, just like many 1980s sitcom parents never received a memo that the 1950s ended. Mr. and Mrs. Putterman live in their own self-obsessed heads and pay more attention to their toys than their family. They love living in a big house on a big hill, as Ric Flair used to say and probably still does say.

The Puttermans take things to an exaggerated, almost otherwordly extreme. They live in a self-contained bubble that causes them to suffer an isolating materialistic existence that consumes them.

“So isolated from the city,” comments a swinger the Puttermans invite home for some swinging.

“That’s what we like about it.” Mrs. Putternman says. (The truly talented Mary Woronov, delivering a superbly professional job in a silly movie.)

“Gets you in touch with the real you.” Mr. Putterman. (Gerrit Graham)

No, it doesn’t. Or does it? Isolating oneself from the rest of the world solely to live a life of materialism and hedonism seems more akin and detaching from society, which doesn’t seem to contribute to self-awareness or growth. If you like that sort of thing and appreciate all the ill effects, then maybe “getting in touch with the real you” reflects an appropriate description. The Putterman’s self-absorbed obsessions with high-tech, indoor swimming pools, a glorious suburban mansion, and all the 1980s status symbols seem weird by even the era’s exaggerated standards.

The toys may also reflect a warning that the “real you” is a troubled person who defines themselves by their toys. Honestly, if you take out the space monster that enters a family’s home through their television, TerrorVision would be a docudrama.

Consumerism leads Mr. and Mrs. Putterman’s lives. They give themselves so much to it that it controls them. Call it a tad ironic that their distance from humanity draws in a creature from outer space that consumes them. Literally.

The consumers get consumed, get it?

It seems unfair to hammer the 1980s for materialism. People from all eras love to purchase things that give them an elevated status, and a Rolls Royce isn’t necessary to deliver something that hypes up someone’s perceived social value. Imagine being the first person to own a TV during the Golden Age of Television.

Such attitudes about possessions persist today, but the 1980s had an entirely different materialistic vibe. The 1980s thrived on one-upmanship. Material possessions not only defined someone but included an added element of winning out by having more toys.

The satellite dish in TerrorVision plays to this idea since a satellite dish offered more than the standard cable package, and it was bulkier and costlier. The dish symbolized excess. With God knows how many channels, the satellite dish reflected a love for unnecessary excess. Welcome to the 1980s.

And welcome to earth, Hungry Beast. Looks like you have a new home.

Home (& Space) Invader

Hungry Beast, the invading, human-eating alien, embodies another element of 1980s pop culture: the creature’s clearly a parody of E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial (1982). This satirical element isn’t entirely subtle. The Putterman siblings, Sherman and Suzy, and Suzy’s 1980s-cliched-heavy-metal-loving boyfriend, O.D., follow the E.T. playbook and make friends with the ravenous interstellar beastie. (Yes, that is a young Diane Franklin playing Suzy.)

Hungry Beast calms down a bit when O.D.’s heavy metal armbands and their studs bring back pleasant memories from the creature’s childhood. (?) The intrepid youth take advantage of the situation by feeding the hungry monster tons of frozen and unhealthy food, suggesting the selections are like vegetables. Hungry Beast agrees and is down with eating high-fat, high-refined carbohydrate unhealthy stuff.

TerrorVision never treads lightly with its satire. Feeding the Hungry Beast junk food further drives home points about consumerism and the constant intake of unhealthy things. Hungry Beast won’t likely suffer from high cholesterol or other issues, but he becomes ridiculously docile after his introduction to a steady diet of junk.

And there’s more. The kids introduce the space creature to television, music, and other pop cultural, consumer-driven pursuits known for time-wasting. The E.T. parody-enthused direction the film takes rushes itself in the final act, but it gets the points across. The kids soon realize they can make money off of Hungry Beast, a decision that proves disastrous. Call this a tip of the hat to Oliver Stone, as their plans to hawk Hungry Beast on a television show backfire. Hungry Beast becomes hungrier and uncontrollable. Junk food won’t smash the urge, so he goes on a rampage. That’s one more 1980s morality lesson about greed for audiences to learn.

TerrorVision Suffers the 1980s Curse

A mildly humorous sequence sees Hungry Beast watching a television broadcast of the 1956 sci-fi classic Earth Vs. the Flying Saucers and laughing his Jabba-the-Hut-influenced butt off at the mayhem and destruction on the tubs. The half Spielberg’s E.T./half Carpenter’sThe Thing creature is out of time and place. So, was TerrorVision. Both theatrically and on the home video market, there wasn’t much demand for a PG-rated sci-fi satirical comedy at the time. Today, things might play out differently. Streaming services and cable TV channels might welcome a cultish, oddball film with a catchy theme song by The Fibonaccis.

Yesterday or today, TerrorVision would benefit one or two script revisions. Adding some edgier material and funnier gags wouldn’t hurt. Still, TerrorVision deserves another look as an oddball 1980s VHS days curiosity.

The filmmakers tried to do something different. Mission achieved.

![“Addams Family Values” Is a Perfect Thanksgiving Horror Film [The Lady Killers Podcast] “Addams Family Values” Is a Perfect Thanksgiving Horror Film [The Lady Killers Podcast]](https://i0.wp.com/bloody-disgusting.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/11/Screenshot-2024-11-21-at-8.34.40-AM.png?resize=886%2C538&ssl=1)

![‘Chicago Med’ Recap Season 10, Episode 8 — [Spoiler] Dead or Alive ‘Chicago Med’ Recap Season 10, Episode 8 — [Spoiler] Dead or Alive](https://tvline.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/11/chicago-med-recap.jpg?w=650)