Kurt Barlow stands in literary, television, radio, and – soon – cinematic history as one of pop culture’s most famous vampires. Incredibly, the character only appeared in one work, Stephen King’s novel ‘Salem’s Lot, in 1975. The vampiric antique dealer made quite an impression on millions of horror fans through his appearances in different mediums.

Those who watched the original broadcast of the 1979 mini-series had to wait a long time for his live-action debut. Barlow, played by Reggie Nalder, made a frighteningly effective arrival in the Tobe Hooper-directed two-parter. Barlow’s appearance shocked viewers as Barlow brutally assaulted the Petrie family in their kitchen. The vicious scene has many similarities to the one in King’s original novel but also significant differences. The same applies to Rutger Hauer’s take on Barlow in the 2004 cable television adaptation. Doug Bradley also took his turn at Barlow’s unnerving kitchen invasion.

All four versions of Barlow’s brutal attack on an innocent family are unsettling. All four deserve a look (or a listen, in Bradley’s case) to examine the underlying subtext that makes the scenes work.

Barlow’s Home Invasion

Barlow’s attack on the Petrie home sees the vampire brutally murder Mark Petrie’s parents. Barlow threatens to feed on the boy as a cross-wielding Father Callahan looks on helplessly. Callahan accepts Barlow’s deal to spare Mark for another night by throwing away his cross to meet Barlow’s “faith against faith.”

What precedes the scene sets up its dramatic and narrative context. Again, differences exist between the novel and the various adaptations. Variances leading into the scene won’t fit the discussion here. The kitchen assault receives an analysis based on how the scene unfolds and underscores the “faith vs. faith” theme.

In King’s novel, the attack fleshes out Barlow’s personality, and the vampire character exudes a mix of arrogance and resignation. Barlow outright admits he seeks a worthy opponent, acknowledging that the teenaged Mark is far superior to the weak-kneed Father Callahan.

Barlow challenges the priest to throw away his cross because it is nothing but a symbol. If Father Callahan truly believes what the cross represents, Barlow should not be able to feed on him. Callahan immediately yields to Barlow’s will – to the vampire’s displeasure. A sneering Barlow refers to Father Callahan as a “false priest,” a biting insult.

Callahan gives in to his fate, knowing his faith failed him. However, Barlow doesn’t feed on Callahan. Instead, the vampire commands Callahan to feed on him. In a mockery of the Christian faith, Barlow provides Father Callahan with rebirth and eternal life as one of the undead.

Grotesquely, Father Callahan now has something far more concrete to embrace than mere faith.

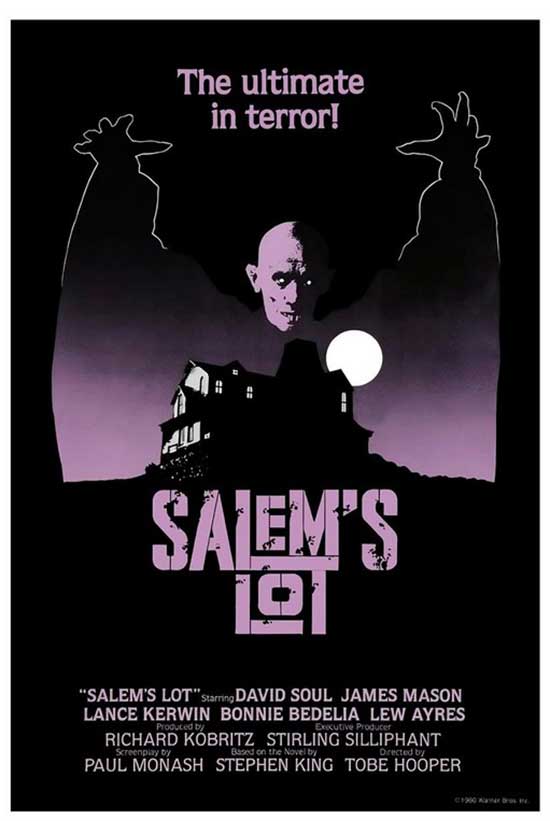

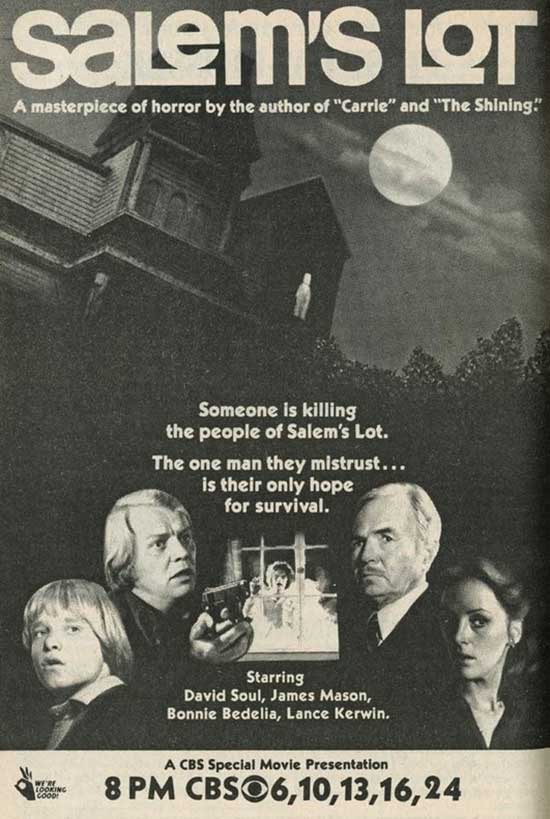

Barlow Finally Arrives in Salem’s Lot (1979)

Nadler’s Barlow’s arrival shocked audiences during the miniseries’ original broadcast. Before the kitchen attack, the character wasn’t seen in the two-hour first part. Keeping Barlow out of the first half created a mysterious buildup to his appearance. Viewers saw other creepy vampires, but not the undead, pestilent leader pulling the proverbial strings.

The scene starts somewhat corny, with très-1970s special effects. Shaking tables, flickering lights, and dishes falling off shelves wouldn’t cut it today. Still, it took little to creep people out at a time when The Amityville Horror (1979) was the rage, and mainstream audiences didn’t suffer from overexposure to CGI and excessive effects.

When a mysterious something crashes through the kitchen window, the audience knows things will get worse during a family’s intervention session with a wayward son.

The old-school make-up job on Barlow is quite effective, allowing Barlow to look menacing and eerie. However, Reggie Nalder’s bestial vampire isn’t Kurt Barlow. He’s a variant on Max Schreck’s Nosferatu. Why anyone made the call to change Barlow is curious. Perhaps the creative hands wanted to shift the dramatic action t Straker, played by the legendary James Mason, rather than split it between two nemeses.

Still, “blue Nosferatu” Barlow is scary and downright vicious. As in King’s novel, he cracks both Petrie parent’s skulls together, killing them in front of their son in a genuinely mean-spirited scene.

“You can do nothing against the master,” intones the human toadie Straker, mocking Father Callahan’s cross-clutching as he attempts to ward off the rat-like, feral Barlow. Callahan knows the situation is dire. Both Petrie parents lay dead on the floor, and Barlow’s sharp fingernails are poised to tear out young Mark Petrie’s throat.

The scene gets across the two essential elements found in the novel. Mark now has a personal stake in killing Barlow, adding dramatic tension to the eventual climax. The underscoring central question of “What is faith?” remains, and Mason’s Straker is positively creepy and eerie in delivering the challenge to Callahan.

As an action-based scene intended to “put heat on the villains,” the scene works brilliantly. However, the thematic element weakens since one protagonist deals with two antagonists. Straker takes Barlow’s dialog, diminishing the conflict and diverting from the faith vs. faith challenge since it deflects from Barlow to Straker and back to Barlow. Even so – Straker and Barlow appear so malevolently smug that audiences can’t wait to hang on until the end to see them meet their demise.

Radio Dreams and Nightmares

Throughout its history, BBC Radio has created exceptional adaptations. (Give a listen to the dramatizations of Batman: Knightfall and Lord of the Rings.) The 1995 adaptation of Salem’s Lot is a somewhat curious choice since it did not capitalize on a work that was currently popular. The novel didn’t experience a resurgence, and 26 years had passed since the previous adaptation.

Kudos to whoever decided to dramatize Salem’s Lot. Casting Doug Bradley, the Hellraiser icon, as Barlow was a brilliant choice. Bradley perfectly conveys Barlow’s arrogance and menace via voice acting.

Bradley’s dialogue follows the novel closely, and the actor lobbies the response to Callahan’s questioning about trusting Barlow and throw down the cross. The words “Well, I trust you.” reflects a brutal sense of superiority. Bradley’s delivery is incredible.

Bradley’s Barlow maintains an angry tone, and he’s enormously dismissive of Callahan, the “shaman,” and his faith. Shaman isn’t the only insult he throws at Callahan. He dismissively calls him “priest” in a disparaging manner.

The “radio Barlow” takes digs at Callahan for his reliance on external items to display his faith, mocking the priest for lacking faith in a superior and resorting to hiding behind symbols. The symbols can’t protect Callahan against Barlow, as they are empty vessels without sincere faith. Barlow knows this and exploits Callahan’s crisis of faith.

Absent visuals, radio theater actors only have their voices and assistance from sound effects to convey a scene. Horrorific isn’t an effective description as much as melodramatic. Bradley’s Barlow comes off as a nasty being because of his smug, condescending attitude, an ironically human attitude. The contempt and condescension add realism to the fantastic scene.

With the third adaptation, the horror-fantasy visuals return to prominence.

The Un-Barlow

Controversy swirls around Rutger Hauer’s portrayal of Kurt Barlow in the 2004 TNT cable television version of Salem’s Lot. (Those controversies extend to alleged behind-the-scenes actions) In truth, Hauer’s Barlow repeats dialog from King’s novel, but he doesn’t deliver the performance with Bradley’s menace. Hauer’s approach and stylish appearance make him a somewhat aristocratic Barlow who conveys a dismissive elitism toward his human victims. In some ways, Hauer’s Barlow seems like a reimaged version of Robert Quarry’s Count Yorga.

When Father Callahan tries to intervene to save Mark Petrie, Hauer’s delivery of the line “Piss off!” conveys his elitism brilliantly. Giving Barlow wall-crawling abilities adds to his creepiness, but the heavy CGI-style neck-breaking of Mark’s mother lacks the realistic cruelty of the 1979 miniseries.

The scene’s central conflict – Barlow vs. Father Callahan – presents a unique dimension lacking in other versions. Barlow literally informs the priest that he cannot win in a faith vs. faith battle because the outcome remains predetermined.

Hauer’s Barlow suggests faith is about casting fate to the wind, hinting the result is typically martydom. Father Callahan can’t win and won’t win because he’s not supposed to win. He’s supposed to die for his faith.

A martyr dies to become reborn in heaven. Father Callahan dies to be perversely reborn in Kurt Barlow’s image.

Yes, Hauer’s Barlow is an evil elitist. He’s also an underrated one.

Hauer isn’t the final Barlow. Alexander Ward’s turn is coming. We’ll see how faithful his portrayal is.

![Mason Ramsey – Twang [Official Music Video] Mason Ramsey – Twang [Official Music Video]](https://i.ytimg.com/vi/xwe8F_AhLY0/maxresdefault.jpg)

:quality(85):upscale()/2023/09/20/695/n/1922564/56736c2a650b12cd78d417.59448204_.jpg)