Perception is everything. Filmmakers often toy with reality by unscrewing the story from the unreliable narrator’s vantage point. In filtering events through a distorted lens, incrementally unraveling the truth, writers and directors keep the viewer tip-toeing through a battlefield littered with dynamite. Darren Aronofsky’s mother! and Mitzi Peirone’s Braid shift reality like tectonic plates. Both are illusory, fever dreams that don’t even seem real. The filmmakers test our mental capacity and push our patience for such absurdism to the absolute limits.

Audiences raked mother! over the coals upon release. A cult classic in many ways, the 2017 horror mystery plunges into allegorical territory, asking the audience to glance deeper into its storytelling elements and below its superficial layers. Its basic conceptual drivers (God, mankind, Mother Nature) mingle in plainspoken verse to mess with your head. Aronofsky ensures the audience is as flabbergasted and delirious as Jennifer Lawrence’s mother, who embodies Mother Earth and has little control over the tragedy devouring the flesh from her bones.

The film sets up its premise in reverse. Him (Javier Bardem) moves about the ash and rubble of a secluded farmhouse to discover a rare crystal. He dusts off the charcoal exterior, polishes it up, and places it upon a nearby mantel. The environment quickly melts away, repairing itself and slowly revealing Mother (Lawrence) cozy in bed. Yawning, she goes downstairs searching for her husband (Bardem), a poet who has moved them into a home far from civilization. The countryside sweeps out in all directions, giving it a real Garden of Eden aesthetic. Bardem’s Him hopes the serenity and silence will inspire him to write again, while Mother spends her free time renovating the estate.

As their relationship flourishes, each finding a sense of purpose and accomplishment, strangers (Ed Harris and Michelle Pfeiffer among them) appear on their doorstep. The disruptors, whose personal turmoil leaks into the lives of their hosts, spread like a disease, multiplying by the day, the hour, the minute. The house, serving as the Earth itself, encases the inhabitants within a fragile ecosystem. As the population grows, the walls crack, and the floorboards buckle under tremendous weight. The film devolves further, as riots break out, cops burst through the front doors, and adoring fans flock to Him, whose talents represent God’s hypnotizing power over generations of followers.

Mother’s perspective is on a tilt, mimicking that of the viewers as they witness reality collapse. The lines between fact and fiction bleed into one another. When Lawrence’s character becomes pregnant, there’s a cosmic shift. The chaos within the home escalates, the walls vibrating with chatter, screams, and mayhem. By the time Mother gives birth to a baby boy, the intruders descend upon her like beasts to prey and snatch the infant up into their arms, passing him around and picking him apart until there’s nothing but a heap of blood and flesh on the hardwood. It’s fiendish and ritualistic.

‘mother!’

With decay spreading like mold, a fire breaks out amid the waves of bodies and swallows Mother whole. She crumbles into a shell of her former self, her beauty now dark and ghoulish. Her carcass becomes one of contempt and sadness. With her final breath, the world fades, dissipating into a suffocating void. The film then recycles, picking back up with the beginning – of time and creation itself. A new perspective emerges, that of a fresh-faced young woman who bears no resemblance to Jennifer Lawrence’s Mother. Aronofsky slaps the audience with deja vu, regurgitating images to impress with the notion that suffering is never-ending. It simply exists as something else. One being falls away, and another is born.

Much of mother! requires a personal shift in perspective. Where many unreliable narrator films include a revelation about reality (such as in the case of this column’s other film), Darren Aronofsky’s story keeps those cards close to the vest, allowing them to go up in smoke with the climax’s fiery armageddon. The audience is as unreliable as Mother, left to parse the layers on their own terms. Without clearly defining reality and fantasy, there’s never that cathartic release – where things are fully explained to the audience. Instead, Aronofsky leaves the viewer hanging in the air, unsatisfied and hungry.

In contrast, Mitzi Peirone’s Braid relies heavenly upon the unreliable narrator twist, alleviating the pressure from the audience and giving them real answers. Playfully preposterous, the picture goes full throttle in its conceit about three friends who play-pretend. We first find Tilda (Sarah Hay) and Petula (Imogen Waterhouse) weighing and packaging drugs to sell on the streets when police sirens pierce the mid-afternoon air. The duo hightail it to the train station and bolt out of town with only one destination on their minds: Daphne’s (Madeline Brewer) sweeping estate. There, they hope to rob their former childhood friend of her inheritance. But they first must play a game.

When Tilda and Petula arrive, they immediately slot into their respective roles as the daughter and the doctor. Daphne, strangely awaiting this moment, turns from her work at the sink and asks Tilda about her school day. Brewer’s slightly aloof performance as the mother instantly drops the audience into her delusional, whirling-dirvish world, one in which child’s play is commonplace and a necessary part of life. Noticing that her daughter might be sick, she fusses over Tilda until the doctor appears on the doorstep. Reality progressively grows more peculiar, as each ensemble player commits to the play-acting. Tilda and Petula’s dedication operates to lull Daphne into a false sense of security until they can find the safe and empty it of its contents.

A psychedelic drug-filled odyssey, the game has three rules: everyone must play, no outsiders allowed, and nobody leaves. Peirone slices the film into sections with each offering glimpses behind the curtain. At present, the film proposes that Daphne has disassociated from reality, exacerbated by her seclusion and loneliness. Her need to play pretend dates back to her youth and a tragic mile marker in her life – a time when the trio played doctor in a treehouse and one fell from the wavering eaves. Shown in a flashback, this moment defines Daphne’s life and leads to a sick obsession with pretend; it somehow eases her anxiety-addled mind, so Petula and Tilda play along for her well-being.

‘Braid’

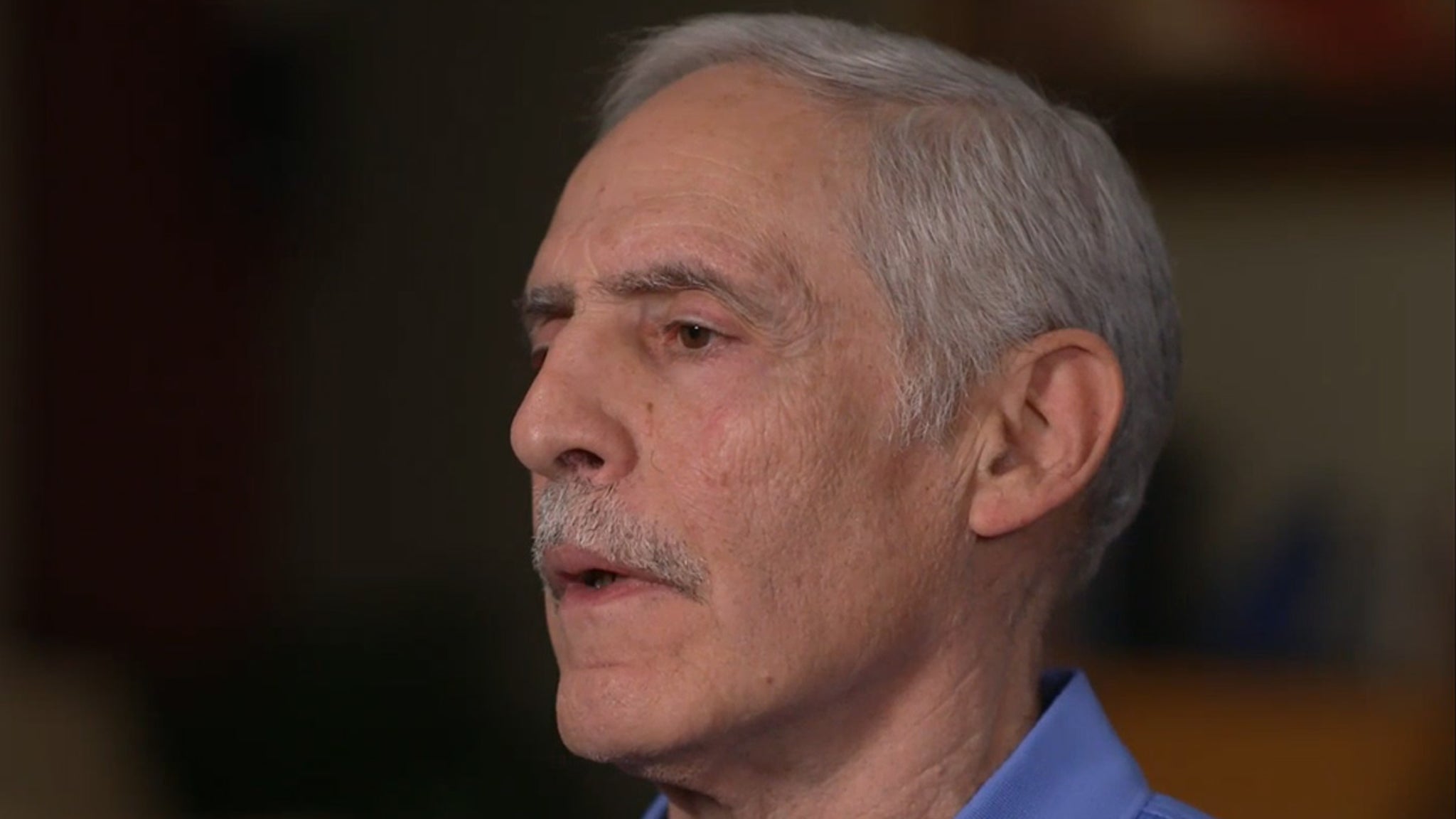

Meanwhile, Detective Siegel (Scott Cohen) makes his rounds to the estate after answering a call about screams being heard on the property. Daphne excuses the occurrences to the fact she’s still adapting to a new medication and promises it’ll never happen again. Siegel has been hunting Petula and Tilda, who’ve been reported missing, and he remains skeptical about her explanation. He’s keenly aware something is amiss, but without proper evidence for a search warrant, he’s unable to press further.

The game slowly winds down to its conclusion, finding Daphne claiming she’s “pregnant” after a sexual encounter with Petula. It’s enough to drive one mad – and leads Petula to convince Daphne she needs a C-section. When performing faux surgery on their friend, Siegel returns to find Petula and Tilda ready to kill Daphne as she lies unconscious on a slab. In a twisted turn of events, Siegel is murdered in cold blood – with Daphne initiating the act. The trio must then bury the body out back and steer his police car into a nearby pond.

Reality comes crashing down upon their shoulders. Siegel’s death triggers the revelation that it has been Petula all along who has lost her sanity. Every part of the film takes place inside Daphne’s mansion, even the beginning when we meet Petula and Tilda and later on the train. It’s all been for the sake of the “game,” which we’re led to believe has taken place over many years. There’s no real purpose other than Daphne proclaiming Petula isn’t fit for the outside world, so she must remain on the estate for the rest of her existence. The film concludes with Tilda arriving home from school again, but this time, Daphne is shown in old age, indicating that the game is never-ending.

In all its weird glory, Braid makes great use of its dramatic unreliable narrator turn. Mitzi Peirone offers bits and pieces of dialogue as telltale signs, and it’s up to the audience to pick up the scent. It’s important the characters believe each version of reality, so much so that they become consumed by the play-acting and perhaps even slip into disarray themselves. While Petula has certainly been conditioned that her runaway lifestyle is real, Tilda and Daphne buy into their other selves to a certain degree. Otherwise, it just wouldn’t work – they must keep Petula contained, or else their perfect little world would be shattered.

mother! and Braid work overtime on the viewer’s mind. To varying degrees, both films immerse audiences in tanks of surrealism, playing upon expectation and in-universe reality. With each flicker of the screen, the stories suck you deeper into a warped, deteriorating fantasy marked by mankind’s self-made delusions. You can agonize over the details and what it all means, but the outcome remains the same: reality has immortalized our fear.

‘mother!’

Double Trouble is a recurring column that pairs up two horror films, past or present, based on theme, style, or story.

The post Is Any of This Real? The Unreliable Narrator in ‘Braid’ & ‘mother!’ appeared first on Bloody Disgusting!.

![Iggy Azalea – Money Come [Official Music Video] Iggy Azalea – Money Come [Official Music Video]](https://i.ytimg.com/vi/7t5V5ygeqLY/maxresdefault.jpg)

Best Shuffle Dance Music Video 2023 on a viral TikTok Song

Best Shuffle Dance Music Video 2023 on a viral TikTok Song