WARNING: The following contains major spoilers for the X trilogy.

Ambitious women are rarely judged kindly by history. Often called cruel or heartless, they’re punished for going after what they want in a way that men simply aren’t. Especially if they choose an unconventional life, eschewing the domestic roles we’ve been told to prize. Women who choose stardom are especially vilified – either picked apart for their physical appearance or for daring to show their authentic selves to the world. And heaven help them if they show any skin. Seductive women may rise to the top, but they do so with labels like harlot, temptress, floozy, and whore.

Bette Davis, one of Hollywood’s most ambitious women, spoke on this phenomenon saying, “In this business, until you’re known as a monster you’re not a star.” This quote introduces Ti West’s MaXXXine, the concluding chapter in a trilogy exploring female ambition. Mia Goth plays both Pearl and Maxine, two women obsessed with international fame. Like many before them, both women are driven by an all-consuming desire to succeed and painted as monsters for daring to act on their own behalf.

‘X’

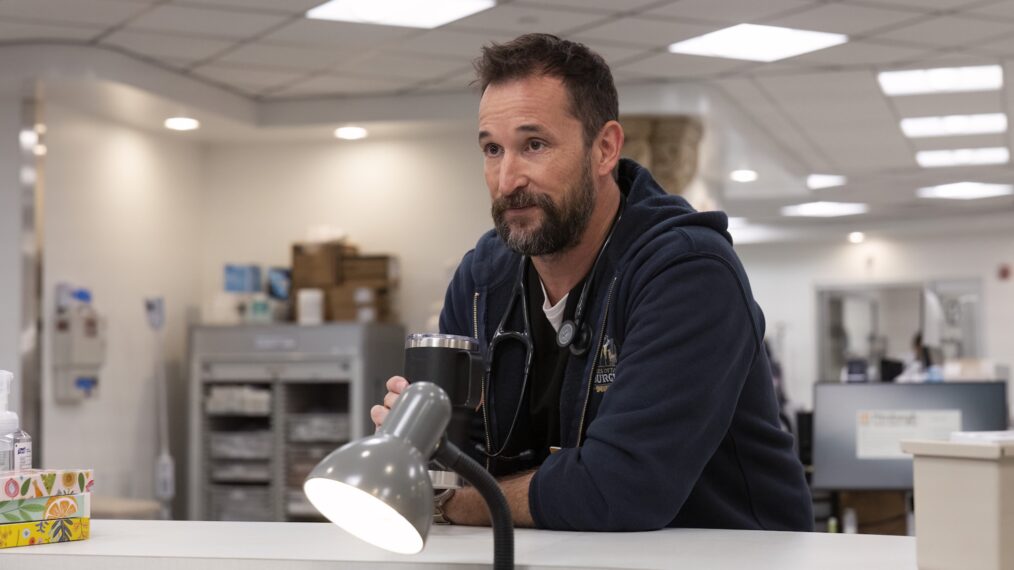

West opens X by introducing us to Maxine Minx in a Texas strip club. The freckle-faced actress does a line of cocaine and declares, “you’re a motherfuckin’ sex symbol,” while staring at herself in the dressing room mirror. She then grabs her suitcase and hits the road, off to film a porno on a rural farm. Her future fiancé Wayne (Martin Henderson) is excited to make a classy adult film and director RJ (Owen Campbell) intends to shoot it with arthouse style. The only fly in the ointment is Lorraine (Jenna Ortega), RJ’s skeptical girlfriend who bristles at the idea of participating in “smut.” But she changes her tune after watching Maxine and her co-star Bobby-Lynne (Brittany Snow) find freedom in expressing their sexuality. They reject the shame society heaps on women for enjoying physical pleasure and refuse to be someone else’s idea of a “nice girl.”

But Lorraine is not the only disapproving woman on the set. Staring from a nearby window is Pearl, an elderly recluse and lady of the house. She invites Maxine in for a glass of lemonade and the two stare at each other from opposite ends of the aging spectrum. Pearl remembers her time as a dancer and mourns the power granted by her youthful beauty. She warns Maxine not to take it for granted and later gazes longingly through the barn window, imagining herself as the star in an explicit scene.

Though now in the waning years of her life, Pearl is still a sexual being and longs for Maxine’s freedom to express her desire. Her husband Howard (Stephen Ure) worries that intercourse will be too much for his heart and gently rejects her persistent advances. But we learn that Pearl has been taking matters into her own hands. Lorraine finds a partially clothed man chained in the basement whom Pearl has been using to fulfill her needs. Later that night, she sneaks into bed with Maxine and caresses her body, seemingly trying to recapture her own youth and beauty through the young woman’s skin.

Though pitiable in some ways, Pearl has become a monster. Enraged by the brazen youth and beauty on display, she unleashes her murderous rage on the cast and kills them all with Howard’s help. But their elderly bodies let them down and both succumb to the stress of these grisly kills. Howard suffers a fatal heart attack while moving a body and Pearl is thrown on the ground by the recoil of her own shotgun. When Maxine understandably refuses to help, the dying woman unleashes a tirade of shame and scorn. She calls Maxine a “deviant little whore” and warns that the would-be starlet will one day end up just like her. But Maxine has heard all of this before. She rejects Pearl’s cruel judgment and crushes her head as she drives off into the sunrise.

Though Pearl is the first film’s primary villain, another monster lurks in the shadows. As the story unfolds, we see snippets of a televangelist preacher raving about his lost daughter, a freckle-faced girl lured away from home. Though we never learn the details of this emancipation, a photo reveals this lost preacher’s daughter to be Maxine herself – her sensitivity to gawkers now making more sense. Raised in an evangelical church, she was likely taught that sexuality is a sin and beautiful women are not to be trusted. But now she’s found a home among people like her, a chosen family who view their bodies as gifts rather than liabilities. In an act of defiance, Maxine turns her father’s own mantra into a cry for freedom, insisting, “I will not accept a life I do not deserve.”

‘Pearl’

West’s imaginative prequel Pearl reunites us with the titular killer in the prime of her life. We journey back to the year 1917 and watch as she languishes in the remote dreariness of her family’s farm. Though she dreams of one day joining a Hollywood chorus line, for now she must be content with performing for the animals as she slops out their food. With her husband fighting overseas and her father infirm, Pearl has no choice but to stay and help with the household chores, her own dreams buckling under the weight of responsibility.

Pearl’s mother Ruth (Tandi Wright) is cruel and bitter, resenting her daughter’s optimistic ambition. She’s hidden her own fancy dresses away and made peace with a life of miserable devotion. But Pearl will not accept her mother’s life. This unfulfilled farmer’s daughter dreams of the day her parents will die and release her of this stifling obligation. She pins all of her hopes on an upcoming dance audition and begins making plans to run away. Like Maxine, she plans to abandon her home and become a star, rejecting a life of rigid control. When her mother forbids her from taking her shot, Pearl pushes her into the fire and leaves her to die. The subsequent murder of her own father speeds along this gruesome emancipation.

Though Maxine’s deadly rendezvous with Pearl is still decades away, the younger woman’s phrase feels particularly apt. Pearl also refuses to accept a life she does not deserve – one in which she is expected to sacrifice her own dreams to take care of the home and her men. In a tear-filled monologue, she confesses to being glad she lost an earlier pregnancy and her fear of one day becoming a mother. Caring for a child would prevent her from following her dreams and Pearl does not want to be saddled with someone else’s needs. She is an ambitious woman who was born way too soon. In 1917, she simply does not have the freedom, mobility, and choice Maxine will later enjoy – and the pain of these limitations drives her to kill.

When the big day arrives, Pearl gives it her all. Though she dances relatively well, we see that she is far from the world-renowned talent she will one day imply. She is summarily rejected and her story becomes one of bitter disappointment and shattered dreams. The producers are looking for a particular type of girl – one with the X factor, preferably blond – and no matter what Pearl does, she will never be right for this particular role. Her frustrating failure is indicative of the restrictive era. Decades later, Maxine will have many opportunities to audition for various roles and an agent to help navigate a powerful system. Though Maxine’s chance at stardom may be slim, for Pearl it is virtually nonexistent. The dance audition truly is her only means of escaping a life she neither wants nor deserves. Though nothing excuses her grisly string of murders, her motive for killing the cast and crew now becomes clear. Not only does she begrudge them their age and beauty, they are living out the dream she was denied.

‘MaXXXine’

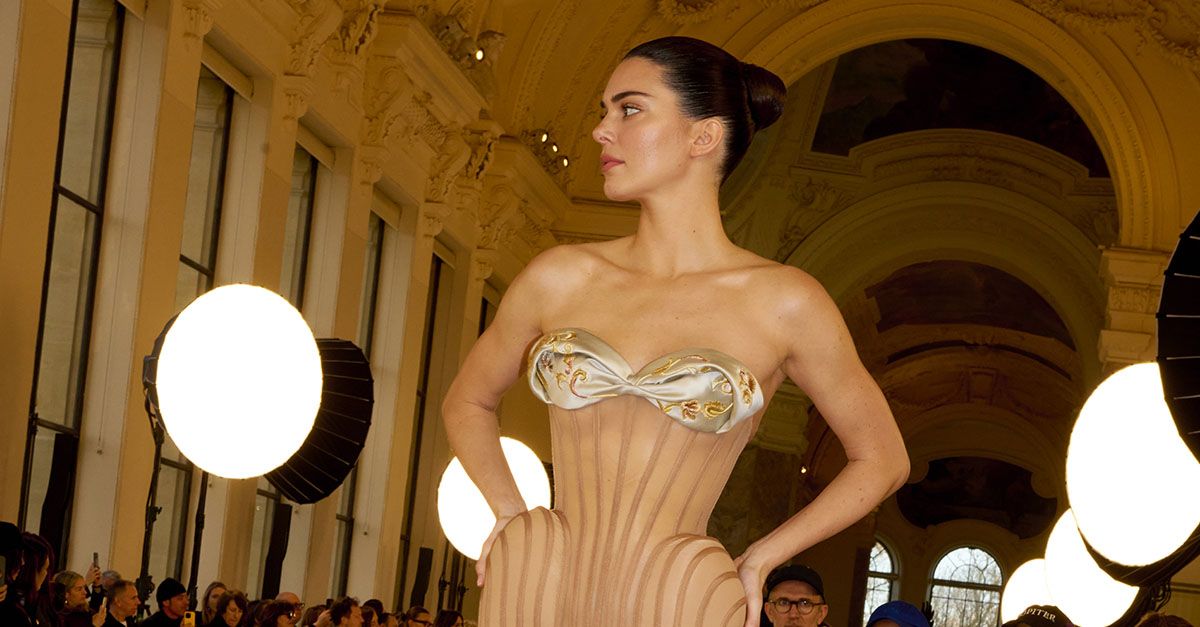

Pearl’s failed audition mirrors the opening scene of MaXXXine, the concluding film of this progressive trilogy. Six years after the deaths of her friends and lovers, Maxine has made it to Hollywood and become a successful porn actress with hopes of breaking into mainstream film. Like Pearl, she performs before an ominous panel with a line of young hopefuls waiting outside. Fortunately, Maxine emerges with a happier outcome. Perhaps due to luck or years spent adjusting to the Hollywood machine, she wins the lead role in a horror film.

But the future star is still haunted by memories of the woman she killed. She remembers the touch of Pearl’s greedy fingers and imagines her looming in distant windows. It’s likely that her dying words still ring in Maxine’s ears and she fears winding up old and alone – with nothing to show for her life but missed opportunities and bitter regret. On set, she meets her ambitious director, Elizabeth Bender (Elizabeth Debicki), also trying to prove herself in a male-dominated field. With brutal frankness, Bender advises her to cut out everything in her life except for the film – she will only have one shot at a breakout role – and it seems Maxine takes this cold guidance to heart.

But a shadow falls over her life as she begins to prepare. Not only does she receive footage of what is now being called the Texas Porn Star Massacre, someone is killing the people who orbit her life. We eventually learn that her televangelist father has returned, tracking down his wayward daughter to save her from a life of sin. Blind to his own hypocrisy, Ernest Miller (Simon Prast) plans to film himself performing an exorcism, believing this will give his daughter the stardom she’s always desired – but only on his terms. He hopes to publicly reject her sinful choices for the world to see and reify his insidious brand of patriarchal dominance.

But the only sin Maxine has committed is the sin of living – a prescient phrase lifted from her audition monologue. She has found liberation in bodily autonomy and is no longer beholden to his oppressive beliefs. Miller sees his daughter’s rebellion as a threat to his entire system of power and can’t understand why anyone would reject his shame-based control. Surely it must be a monstrous demon tempting her away and not an understandable desire for freedom. His patented phrase now feels particularly ironic and we realize it’s his lifestyle she’s been trying to escape. Miller expects his daughter to return to his ultra-conservative home and revert to the dutiful “nice girl” who subjugates herself to men. But Maxine deserves a better life and she will do anything to escape his grasp.

We leave Maxine as we first met her – doing cocaine and reminding herself that she is a star. Not only has she survived two murderous psychopaths, she’s fought tooth and nail to accomplish her goals. Though terrifying, it seems her encounters with Pearl and Miller have put this liberty into perspective. She’s well aware of how lucky she is and vows not to take a single moment for granted. It’s tempting to wonder where Pearl would end up if she were born as a part of Maxine’s generation. Would she also have found a way to leave her conservative family behind? Perhaps if given just a few more tries, she too could land a role that would be her big break. But Pearl is limited by the time in which she exists – not to mention a heavy dose of sadistic psychopathy. Though both women kill in pursuit of their dreams, their outcomes differ wildly in part due to the eras in which they exert their power. Pearl’s ambition turns her into a monster while Maxine’s determination makes her a star.

:quality(85):upscale()/2025/01/30/728/n/1922564/bae21b97679ba8cf1dcb88.10828921_.png)

![Iggy Azalea – Money Come [Official Music Video] Iggy Azalea – Money Come [Official Music Video]](https://i.ytimg.com/vi/7t5V5ygeqLY/maxresdefault.jpg)