ComingSoon Editor-in-Chief Tyler Treese spoke with Miller’s Girl director and writer Jade Halley Bartlett about the Jenna Ortega and Martin Freeman-led movie. The filmmaker spoke about directing Jenna Ortega and incorporating legendary authors. Miller’s Girl is now playing in theaters.

“A talented young writer (Jenna Ortega) embarks on a creative odyssey when her teacher (Martin Freeman) assigns a project that entangles them both in an increasingly complex web,” reads the movie‘s synopsis. “As lines blur and their lives intertwine, professor and protégé must confront their darkest selves while straining to preserve their individual sense of purpose and the things they hold most dear.”

Tyler Treese: In Miller’s Girl, you’re not afraid to dive into and really explore that gray area within what happens in the film. What did you most enjoy about not having something over-the-top or extreme happen but having these two sides explored? Lines are crossed, and there’s a lot to explore there.

Jade Halley Bartlett: That’s a great question. This movie is a character study more than it is a decree about anything. I think that these situations happen all the time, and I think it’s more … this is closer to how these situations actually happen than the capital-V villain, capital-V victim situation. Not that those don’t happen — they do happen often, but I think, at least in my experience, this kind of stuff is the stuff that gets talked about less, and these lines that are crossed are still crossed lines, you know? I wanted to explore the characters within that without being … I didn’t need a massive tipping point because the tipping point is subjective to these characters. This is all from Cairo’s perspective.

Cairo lives in a big mansion. Her parents are globe-trotting. All of the books that she reads amd the movies she watches are 18th, 19th, and 20th century. They’re inherently problematic because they sell the great lie of romance, so when she comes into the real world and meets with this person that she idealizes, she’s wrong. She’s not equipped to handle what he does. And what he does is reprehensible. I mean, he humiliates her — he definition gaslights her. But she’s an isolated person with no concept of consequence. So, of course, her reaction to that … she’s never experienced heartbreak before. Her reaction to that is going to be incredibly violent. It’s not intended to be … this isn’t realism, like, the movie isn’t naturalistic. It’s intentionally three feet off of the ground. It’s intentionally supposed to feel like a dark fairy tale.

Because I think young girls, or at least I was, deeply to terribly, ludicrously romantic. There’s a lot of horror in that. I describe this movie as a romantic horror. It’s been called a thriller, which I think is misleading. I don’t know that it’s really a thriller. I think it’s just a terrifying character study of people who make a lot of wrong choices and people who aren’t the perfect victim or the perfect villain. Both of those things are kind of boring to write. I think they’re boring to play as actors, but real people exhibit all of those things. Real people are morally and ethically gray, so I wanted to have the reality of that set in a world that was three feet off of the ground.

One aspect that I’ve been thinking about since I saw the film was Cairo’s in this small town. Like you said, her parents are away, and she’s very much alone. How much of her situation do you think kind of comes from boredom and not really having something to do?

Oh, I mean, so much of it. Boredom is not the word I would use, but the word she uses is longing. I think she’s desperate to be seen. Every good Southern Gothic has a ghost, and that’s what she is. I think she’s longing so desperately to be seen. She’s so much smarter than everybody around her. She should be at an excellent private school in the city, but she’s at this now. It is a beautiful school, but she’s at this country bumf–k school in the middle of nowhere in Tennessee. So she’s just not challenged in the way I think she should be. I don’t think she does anything out of boredom. I think she does it out of a real intention to feel something quite deeply.

But she’s also the type of character who — and I don’t think young girls are given enough credit for this — is so intelligent that, and because she’s so isolated, she keeps her emotionality as something that she holds almost in her hand, not something that’s inside of her. So she wants so badly to feel the same way a ghost wants to have flesh. She wants to feel and be seen. It drives her to do things that, if she’d had any other experience or was equipped to handle any of it, she probably wouldn’t have done. She probably would’ve been like, “Well, this is ridiculous, and what am I doing? This man is not it.” But she doesn’t.

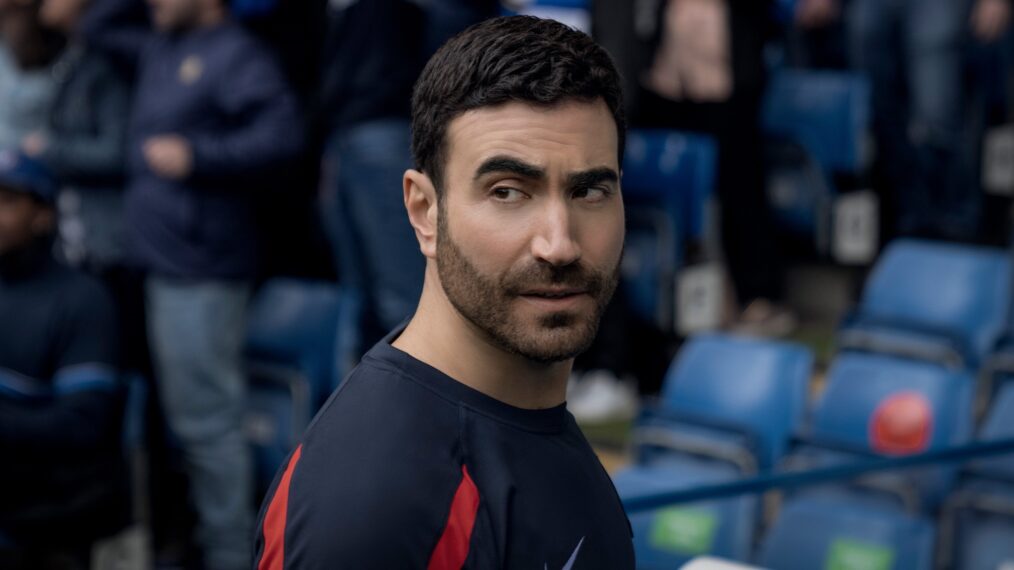

Jenna Ortega is so great in this role, and it is such an interesting character for her to play. What did you like most about what she brought to the character of Cairo?

Well,, I’d always wanted this character … I don’t want to say the birth of a villain, because villain is the wrong word, but maybe the birth of an antagonist. I wanted to watch this young person watch their heartbreak metastasize and then kind of turn into a bug. They kind of go through Kafka’s The Metamorphosis. By the end of the script, Cairo is not the same person she was at the beginning. It’s very easy to take Cairo and make her really melodramatic because the language is so heightened. But Jenna made it feel very natural. Even though she is sort of completing the transformation by the end of the film, you can still feel her heartbreak inside of her. There’ are still pieces of humanity that shine out of her.

And I think it’s very sad. I think it’s devastating. I think she’s also terrifying, without any spoilers. There’s the scene with her and Winnie where they’re passing a bottle back and forth, and there’s a photograph, and you watch her make a decision. You watch Cairo make a decision at that moment and Jenna’s whole face changes. The way she’s looking at the whole situation changes. But what’s astounding is that we shot the movie out of order, so she was able to make a choice in a scene way before we did the other scenes and carried it through. She’s a savant. She’s incredible.

I found it really interesting that Henry Miller, the author, was incorporated into the story, and she tried to emulate his style and all the trappings coming into this story. Are you a fan of Miller’s work?

Oh, I’m a huge fan of Henry Miller and also Anaïs Nin. I wish I could remember the name of the book, it’s her diary of their relationship. They were both writers and I think that this diary is a massive influence on writing the script, because they were both very different writers. Henry’s such a masculine writer, but he’s got such a clever turn of phrase, and he’s so funny. I think he’s quite charming. And Anaïs is wrought iron. She’s like curdling smoke. She’s the cat that slinks around your ankle. So the coming together of both of their works and the way they would talk about each other’s work, I found so engaging. I think it’s so romantic. It definitely was an influence between these two characters.

The work of Henry Miller’s that’s in Miller’s Girl, Under the Roofs of Paris, is not Tropic of Cancer. He has these esteemed novels — Under the Roofs of Paris, he got paid. It was smut, you know? It was intended to be smut. But even within that smut, I think his turn of phrase is so good, but Jonathan should have known better. And I, personally, as a reader, found it … I don’t know if funny is the word, but Jonathan sees that book on her desk, and then when she says she’s going to ride in the style of Henry Miller, he should have known exactly what she meant, but he didn’t. He’s incapable of seeing what he is.

You wrote the script, and this was your directorial feature debut. I was curious if anything surprised you about the entire process?

What really surprised me was I was an actor and I’m a writer. What really surprised me is how much I enjoy directing. Directing feels more natural to me than writing or acting. I think writing and acting are incredibly hard. That’s like blood magic. It requires a lot of bleeding to do, and directing requires an objectivity to be able to be able to get things done. It felt emotionally safer than writing or acting did. Because I did those other two things, it was really easy for me to articulate what I wanted to see to our heads of department, to the executives, and to the actors. So the movie looks exactly like I had pictured it. Everybody understood the assignment.

I wish I could say I had real challenges. I didn’t. It was kind of an anomaly of near perfection. I’m just so grateful. I mean, I made a movie! [Laughs]. I can’t believe I made a movie. I’m still kind of a little twinkly-eyed about it because it happened. I had the most incredible cast and crew and executives, and I’m just thrilled.

![Mason Ramsey – Twang [Official Music Video] Mason Ramsey – Twang [Official Music Video]](https://i.ytimg.com/vi/xwe8F_AhLY0/maxresdefault.jpg)