I admit, it didn’t look good. My two-year-old daughter was lying on her back beating her sparkly jelly shoes against the ground, hands balled up in fists, cheeks streaked with tears. My husband was with her, he’d drawn the short straw while I’d escaped with the task of securing our restaurant reservation. The table had a perfect view of the sun setting over the Greek island, and the slope where my daughter was screaming.

Next to me, two British couples sipped white wine and beer. At first, I didn’t pay much attention to their comments—“What’s wrong with that girl?”; “Where’s her mother?”—it was nothing I hadn’t heard before. But very quickly, the conversation took a different turn. “He’s not even trying to cuddle her. He’s just sitting there.”

It was true, my husband wasn’t trying to cuddle her. He knew, as did I, that at this stage of the tantrum, approaching her would set off another round. But he wasn’t “just sitting there.” He was whispering to her. I knew what he was saying because we said the same thing whenever she had a tantrum: “You’re okay, baby, you’re okay, I know you’re angry but we’re here. When you’re ready, we’ll give you a cuddle.”

Then one of the men said something that made my mouth fall open. “He’s obviously not the father. He looks nothing like her.” I watched him slide an olive into his mouth. “What if he’s kidnapped her? She’s fighting and we’re all just watching.” He pushed his aviators to the top of his head and reached for his phone. “That’s it. I’m calling the police.”

How to describe my daughter? She’s fiercely intelligent. She’s strong-willed. She has the heart of a lion, the wiles of a fox, and the memory of an elephant—if you promise her something, you’d better deliver. She’s beautiful. Her hair is chestnut and lightens in the summer. From a distance, her eyes look brown but up close, they’re flecked with amber. She is all these things because she is entirely herself and because she is our daughter. I am Singaporean-Chinese—petite, dark brown hair, dark eyes. My husband is white British—tall, blonde, blue eyes.

The incident in Greece was not the first time I’d been confronted with the complexities of race. As a South-East Asian woman living in London, race is inescapable. I was afraid to go out when COVID hit. I’m catcalled in a mish-mash of mispronounced one-liners. I’m told to go home. I’m constantly mistaken for other Asians. A woman once informed me that I was Japanese. I must have looked confused because she proceeded to spell out “Japanese.” I didn’t tell her that I was a lawyer and a writer and that both these things are profoundly at odds with the inability to spell. She didn’t seem particularly interested in facts.

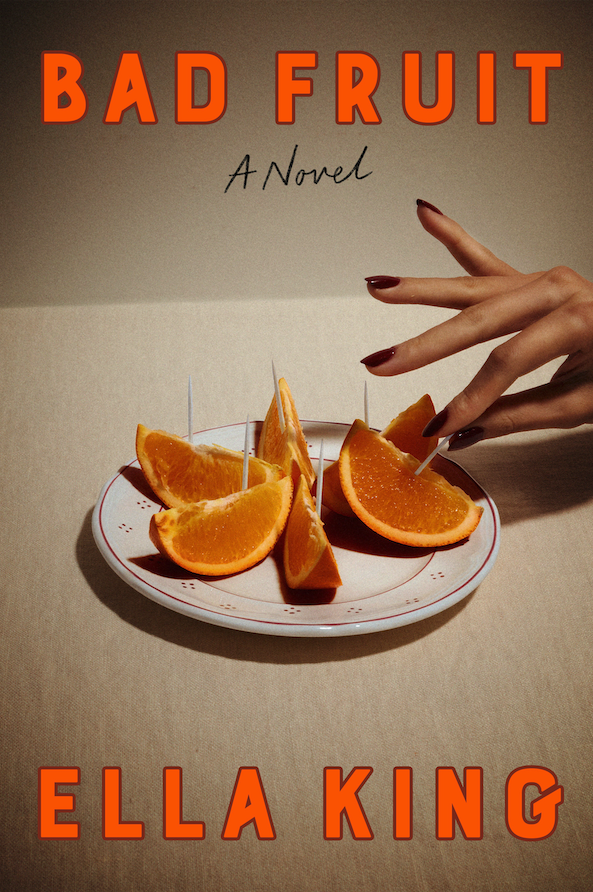

As a South-East Asian author, race is also inescapable. Like most writers, I portray characters that reflect my own background. In the first drafts of my novel, Bad Fruit, my protagonist, like me, had Singaporean parents who migrated to the UK. I wanted to capture the liminal space that second-generation immigrants occupy—the right accent but not the right skin tone, the same schooling but not the same school experience. The sense of never quite belonging to a white world or an Asian one.

As a South-East Asian woman living in London, race is inescapable.

But the scene in Greece made something painfully clear: My experience as a South-East Asian in a predominately white culture was vastly different from my daughter’s experience as multiracial. However much I felt different from my parents, I didn’t actually look different. My appearance had never been grounds for the reporting of a crime.

This avid fascination with how white my daughter is, how Asian, how she looks like her parents, how she doesn’t, isn’t restricted to white Brits on holiday. It comes from my side of the family, too—Asian relatives who regularly dissect my daughter’s features down racial lines. “The shape of her eyes is Chinese but not the color.” “Her cheeks and nose are ours but not her skin.” When I hear these words, when I remember them, a desperation flares inside me, makes me clasp my daughter to my chest. I feel the same spark of danger I felt in Greece, like she is about to be cut adrift. She is only five.

After the incident in Greece, I replayed the scene many times in my head, trying to figure out what I should have said. Sometimes, I practiced patient education: “Do you understand how damaging your racialization is? Do you see how it excludes her from us?” Other times, I practiced rage: “Do you want to line my family up in color order? Would you do this to a white girl?” Looking back, I can see I was punishing myself. Because, in the moment, I’d said none of those things. I’d stood up, shaking as I pushed my chair back, and begged: “Please don’t call the police. That’s my husband and my daughter. She’s just having a tantrum.”

Months went by of me doing this to myself, of going over and over what I didn’t do, how I could have done better, until during an early morning writing session, I realized something. The man, my Asian relatives, every person who’d hurt my family through their microaggressions, their outright racism, had done it with words. But I had words, too. Words that might one day be published, words that had the potential to reach thousands. So I made a decision. I changed my protagonist’s race from Singaporean-Chinese to multiracial. I wrote about colorism. I told a story about a child who is consistently othered from her parents.

I know it’s just fiction; I know it’s just words. But I hope that my words, joined with thousands of other diverse voices, might raise a choir so loud, it could be playing the next time a man at a seaside restaurant thinks about reporting the kidnapping of a little girl having a tantrum with her father. It could be exactly what convinces my daughter to refuse to fracture herself into the white, the Asian. It could convince the millions of multiracial children to think, I am wholly myself. Astonishing, unique. Indivisible.

Bad Fruit by Ella King is published by Astra House and is out on August 23, 2022.

![Mason Ramsey – Twang [Official Music Video] Mason Ramsey – Twang [Official Music Video]](https://i.ytimg.com/vi/xwe8F_AhLY0/maxresdefault.jpg)