Receive free Pensions updates

We’ll send you a myFT Daily Digest email rounding up the latest Pensions news every morning.

The writer is a former global head of asset allocation at a fund manager

The goals of the pensions reforms outlined last week by UK chancellor Jeremy Hunt are noble enough — they are to lift both productivity and pension savings.

The reforms seek to do that with a pact among a number of large financial service firms to allocate at least 5 per cent of their defined contribution default fund client assets to unlisted equities by 2030.

But his big idea rests on a couple of key assumptions. First, that a lack of equity capital is holding back unlisted high growth companies from flourishing. And second, unlisted equities deliver higher returns than their public market counterparts.

The evidence for the first claim is circumstantial. When it comes to venture capital the UK is no minnow. KPMG estimates that last year almost $35bn of deals were done in the UK — more than the total completed in France and Germany combined. But when it comes to later-stage deals worth more than $100mn, analysis by New Financial finds fundraisings are dominated by international VCs. In a global market for growth companies, capital is available. It’s just not particularly British. That said, it’s not hard to infer that the cost of international due diligence raises the cost of UK growth company capital at the margin.

Moreover, the UK does appear to have a problem scaling-up unlisted firms. British Patient Capital — a subsidiary of the state-owned British Business Bank — reports that while deal sizes are comparable for US and UK start-ups in their first round of funding, by the fifth and sixth rounds American deal sizes are around three times larger than their British counterparts. It’s not clear whether the problem is the availability of capital, but a cheaper cost of funding won’t hurt.

The evidence for private equity generating superior returns to public equity appears at first glance to rest on firmer ground. The overwhelming consensus from international investment managers’ capital market assumptions is that private equity will be the highest returning asset class over the long run. For example, BlackRock projects private equity to outperform US stocks by more than 3 per cent a year over the long-term; Morgan Stanley expects 4.6 per cent a year and JPMorgan Asset Management 2 per cent.

Part of the stated methodological rationale for expecting private equity outperformance is the sheer awfulness of the asset class’s liquidity. You can’t get your money back when you want it. Such disutility must come with a cost, forecasters figure, and they project this cost as a higher expected return. Illiquidity premia are easier to assume than to measure.

In the context of exceptional recent private equity performance, this might be forgiven. But if returns were flattered by 15 years of cheap debt, then the assumptions of investment managers will prove simply extrapolative rather than predictive in a new age of higher bond yields. Nonetheless, large investors such as the Wellcome Trust have achieved spectacularly good returns over the past decade.

When measured over longer periods, the returns to high growth private equity strategies have been more varied. Even large and sophisticated investors like Calpers have seen VC portfolio returns average below 1 per cent a year over a 20-year period. And, unnervingly, academic studies find almost universally that returns from private equity don’t beat public markets, after fees. Professor Ludovic Phalippou of the Saïd Business School has called the industry a billionaire factory, where the billionaires are the fund managers rather than the entrepreneurs.

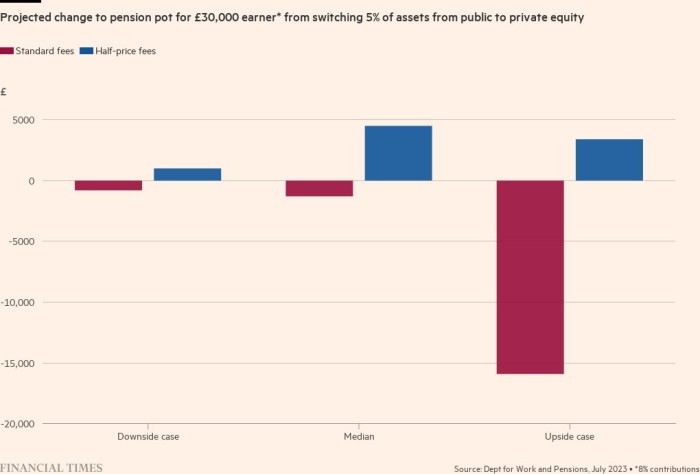

But inspecting the fine print, the government costings analysis does not rely on heroic return forecasts. In fact, they project that defined contribution pension pots will be slightly smaller if they make the switch from public to private equity, once fees are taken into account. The fees are substantial, with a 5 per cent allocation to private equity more than doubling their cumulative total paid over 30 years in the median projection from £10,700 to £22,500 per pension saver.

As such, Hunt is forced to rely on a supplementary forecast in which private equity firms charge UK pension managers only half their standard rate to clear his “golden rule” of securing the best possible outcomes for pension savers.

The chancellor’s desire to help crack two hard problems — the difficulty that companies have scaling up from start-up to listing, and low prospective defined contribution pensions returns — should be applauded. If he can force down private equity fees to a level where the asset class outperforms public markets even in a higher yield environment he will have cracked a third.

![Mason Ramsey – Twang [Official Music Video] Mason Ramsey – Twang [Official Music Video]](https://i.ytimg.com/vi/xwe8F_AhLY0/maxresdefault.jpg)