High childcare costs are forcing parents who want to become nurses in England to quit their training or reject joining the profession, at a time when the health service is suffering from acute staff shortages.

Trainees do not have access to the 30 hours of free childcare support for working parents of three and four-year-olds, which will be expanded from April to all infants aged over nine months until the child starts school.

Health leaders have asked the government to “urgently” increase childcare allowance grants to support mothers re-entering work.

“Nursing students are the future of our health and care services, but the future looks bleak with fewer people expected to take up nursing courses this year,” said Dr Nichola Ashby, deputy director of nursing at the Royal College of Nursing, which represents the profession in the UK. “Ultimately, it’s patients who will suffer.”

Ashby said nursing students had reported being forced to drop out because they struggled to afford and access childcare while in training. “Currently, they don’t come close to covering the cost,” she said.

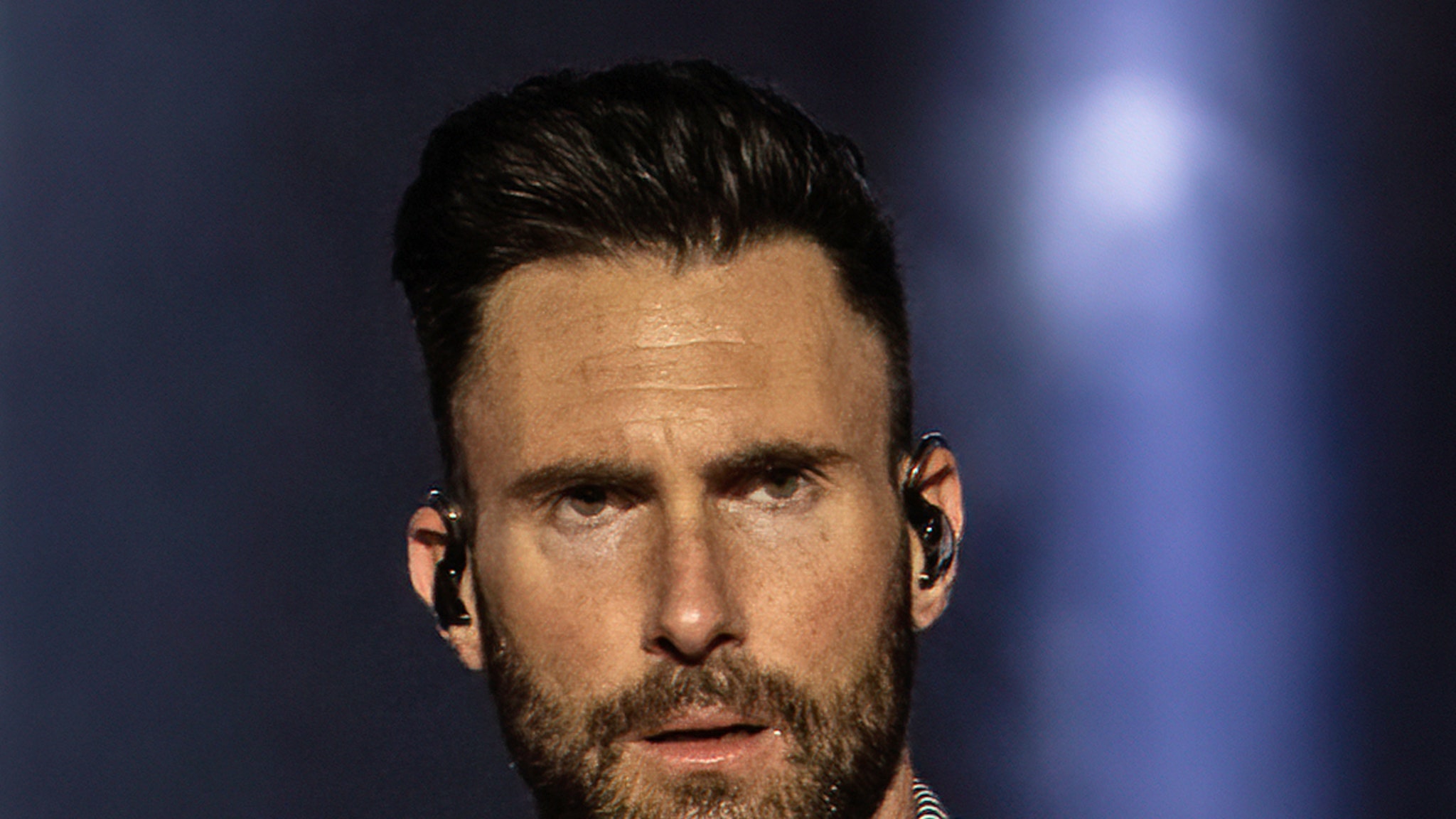

With more than 42,000, or one in 10, unfilled nursing vacancies in NHS trusts in England alone, student nurse and single mother-of-two Leanne Bibby, from Cambridgeshire, had been determined to qualify.

The cost of childcare, however, forced the 30-year-old to contemplate quitting at several points over the past two years. Juggling these expenses with her studies had been a “nightmare” at times, she said.

Many aspiring nurses, like Leanne, said the situation made it more difficult for them to enter the roles needed to keep the health system afloat.

“It has been suggested to me during my training that I should hold off . . . until my children are older,” she said. “At times, it’s been a nightmare, but I know how much the NHS needs nurses.”

The government’s current childcare package is only open to working parents who earn above £8,670 per year and less than £100,000, meaning Leanne is ineligible.

“I do get a childcare grant of 85 per cent [of total childcare costs],” said Bibby, who has a six-year-old and a four-year-old, with another on the way. “However, the remaining 15 per cent still comes to almost £400 per month.”

“If the 15 to 30 funded hours for nine-month-olds covered students, it would take away that added stress so we can focus fully on our studies”, she said.

The calls for the childcare allowance scheme to be extended to students with children come months after the sector experienced a sharp drop in acceptances to study nursing at university last year.

In 2023, the number of acceptances on UK nursing courses fell 12 per cent year on year, according to the university application service UCAS, leaving the government far adrift of its target to boost recruitment.

Under the NHS’s long-term workforce plan for England, nursing training places need to increase 65 to 80 per cent above last year’s levels to meet 2031 targets.

The Department for Education defended its offering, pointing to existing support for students who are also parents.

It said trainees were entitled to a grant that covered 85 per cent of childcare costs across the full year including holidays, up to a maximum of £188.90 per week for one child or up to £323.85 per week for two or more children.

“Student nurses also qualify for an additional NHS grant of £5,000 per academic year, and a further £2,000 on top of that for students with children, which can be used to cover childcare costs”, the department added.

Another trainee nurse and single parent, who asked to remain anonymous, used four food banks in the week before Christmas to provide for her three children.

“You’re required to be on the ward for seven o’clock in the morning, so I’ve really struggled,” she said. “I cannot go and work 37 hours on clinical placement each week and then work to earn extra income that’s going to help me cover these additional costs.

“The lack of support has an impact on what food I can buy, the clubs that my children can attend”, she added. “I don’t think it will be too much to ask for 100 per cent of childcare costs to be paid . . . Nursing needs reform to make it more supportive for mothers.”

Victoria Benson, chief executive of Gingerbread, a charity for single-parent families, said single parents who wanted to retrain should be offered free childcare “so they can take on employment that matches their abilities and interests, pays well and offers security for them and their children”.

Single parents often had to retrain because they needed flexibility, said Sarah Ronan, director of the Early Education and Childcare Coalition advocacy group.

“Investing in childcare now gets more parents into work, which would have a ripple effect on the economy,” she said.

![Mason Ramsey – Twang [Official Music Video] Mason Ramsey – Twang [Official Music Video]](https://i.ytimg.com/vi/xwe8F_AhLY0/maxresdefault.jpg)