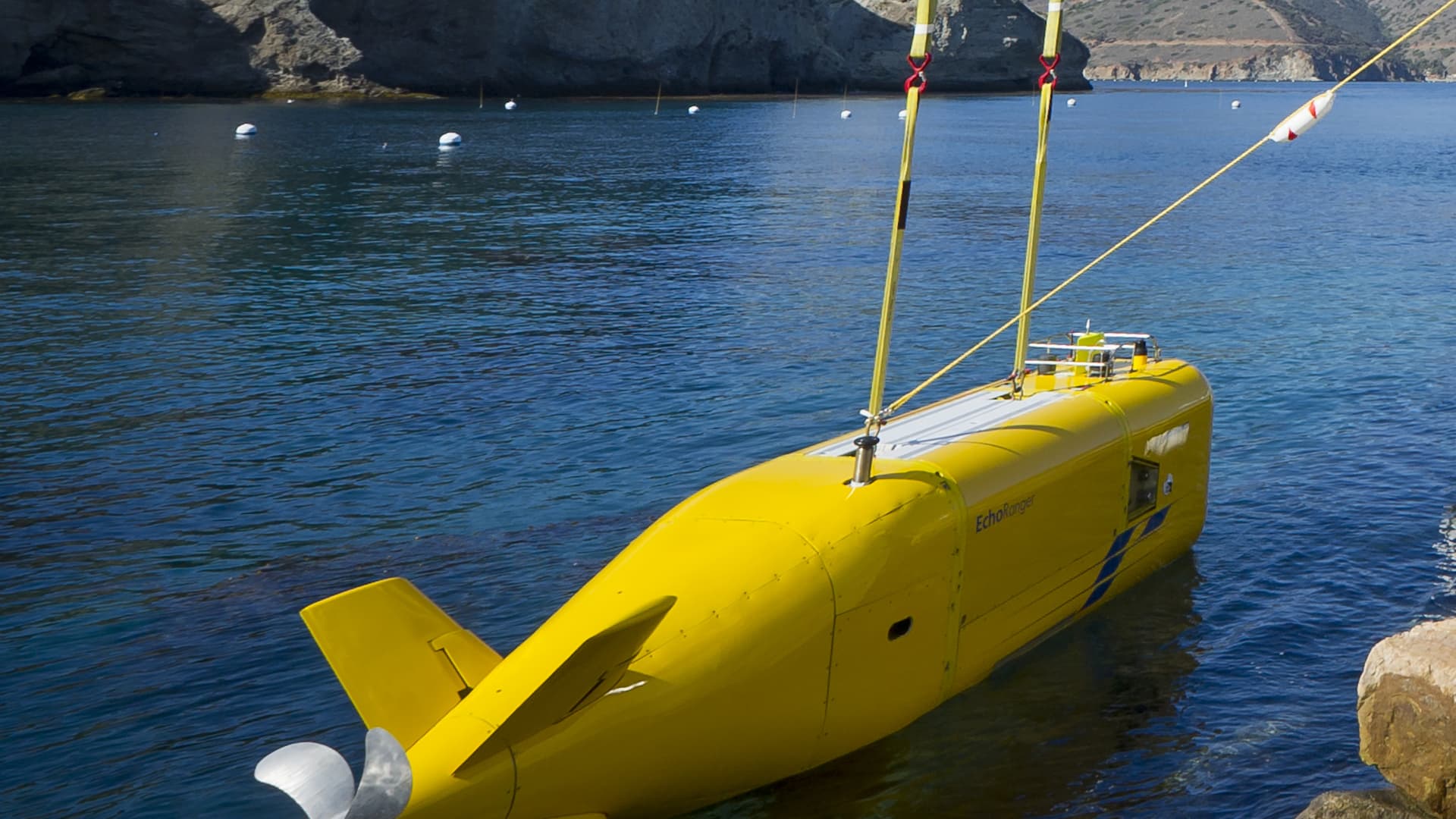

Boeing’s lineup of unmanned, undersea vehicles (UUV) can operate autonomously for months at a time on a hybrid rechargeable propulsion power system. Pictured above is the 18-foot Echo Ranger. The aerospace and defense contractor also makes the 32-foot Echo Seeker, and its latest innovation, and the largest autonomous sub, is the Voyager at 51-feet.

Boeing

More than 80% of the ocean remains unexplored by humans but could soon be mapped by autonomous underwater robots. But is that all unmanned submarines will be used for?

Autonomous robot submarines — also referred to as autonomous underwater vehicles, or AUVs — are able to explore high-pressure areas of the ocean floor that are unreachable by humans through preprogrammed missions, allowing them to function without humans aboard, or controlling them. They’re often used by scientists for underwater research as well as oil and gas companies for deep water surveys, but as defensive security threats continue to grow, the largest sector in the AUV market has become the military.

AUVs can be helpful tools in military ocean exploration, obtaining critical information such as mapping the seafloor, looking for mines — a current use case in the Russia-Ukraine war — and supplying underwater surveillance. Navies worldwide are investing in unmanned underwater vehicles to elevate their fleet of below-water defense tools.

Defense company Anduril Industries kickstarted its expansion from land to sea when it acquired AUV manufacturer Dive Technologies in February. The acquisition gave them a customizable AUV of their own called the Dive-LD.

“There are more and more threats that are on top of the water and under the water that can really only be addressed by robotic systems that can hide from enemy surveillance, that can hide from what you can see in the air and can do things that are only possible to do underwater,” Palmer Luckey, Anduril Industries co-founder, told CNBC’s “Squawk on the Street” at the time of the acquisition.

In addition to the Dive Technologies acquisition, Anduril Industries expanded to Australia in March, then in May partnered with the Australian Defense Force to work on a $100 million project to design and create three extra large AUVs for the Royal Australian Navy.

In the U.K., the Royal Navy recently ordered its first AUV named Cetus XLUUV from MSubs, which is expected to be completed in about two years. The U.K.’s Ministry of Defence also announced in August the donation of six autonomous underwater drones to Ukraine to aid in their fight against Russia by locating and identifying Russian mines.

China recently completed construction on the Zhu Hai Yun, an unmanned ship made to launch drones and that utilizes artificial intelligence to navigate the seas with no crew required. The ship is described by officials in Beijing as a research tool, but many experts expect it to also be used for military purposes.

Boeing has been working on AUVs since the 1970s and has collaborated with the United States Navy and DARPA on a number of underwater vehicle projects in recent years. The Echo Voyager, Boeing’s first extra-large unmanned undersea vehicle, first began operating in 2017 after about five years of design and development. It’s 51-feet long with a 34-foot payload that is approximately the size of a school bus and can be used for oil and gas exploration, long-duration surveying and analyzing infrastructure for oil and gas companies.

Boeing’s latest unmanned, undersea vehicle (UUV), the 51-foot Echo Voyager.

Boeing

The AUV has spent almost 10,000 hours operating at sea and has transited hundreds of nautical miles autonomously. It’s versatile and modular, Ann Stevens, the senior director of Maritime Undersea at Boeing, said in an interview.

“There is no other vehicle of that size and capability in the world, Echo Voyager is the only one,” Stevens said.

Boeing has been in the process of developing the Orca XLUUV with funding from the United States Navy. The company won a $43 million contract to build four of the AUVs, which are based off of the design of Boeing’s Echo Voyager, in February 2019. The project has experienced some production delays – the Orca XLUUVs that were originally scheduled to be delivered in December 2020 are now planned to be finished in 2024. The company cited cost concerns as well as supply chain issues due to the pandemic as reasons for the change.

“It’s a development program, and we’re developing groundbreaking technology that’s never been built before,” Stevens said. “We’ve been in lock step with the Navy the whole way. We’re going to have a great vehicle that comes out the other end.”

Robotics and automation in general is a young field, according to Maani Ghaffari, an assistant professor in the Naval Architecture and Marine Engineering department at the University of Michigan. Researchers began developing AUVs around 50-60 years ago, though the quality and variety of sensors that were necessary to build the systems were limited. Today, sensors are smaller, cheaper and higher quality.

“We are at the stage where we can build much better and more efficient hardware and sensors for the robots to the extent that we’re hoping to deploy some of them in everyday life at some point,” Ghaffari said.

AUVs still have some challenges to overcome before they’re a feasible mechanism for everyday use, for one, the robots have to function in an arguably harsher environment than air, where the water’s higher density creates hydraulic drag that slows down the robot and drains its battery faster.

However, some AUVs in development have impressive speeds and endurance. When it is completed, Boeing said it expects the Orca XLUUV to sail 6,500 nautical miles without being connected to another ship. Anduril reports that the Dive-LD can be sent on missions autonomously for up to 10 days and is made to last for weeks-long missions.

Environmental challenges are the main problem spots for AUVs. Underwater communication from the unmanned submarines is limited as signals used to transfer messages in air get absorbed quickly in water, and cameras on the vehicles are not as clear underwater.

Whether AUVs will eventually be used as more than a surveillance tool and engage in underwater warfare is more of a question of ethics within artificial intelligence and robotics, Ghaffari said. While the vehicles may be sophisticated enough to make autonomous decisions, concerns arise when the decisions may impact human lives.

“The one idea is that you basically pass the battle to these robots instead of soldiers – less people might die, but on the other hand, when the artificial intelligence can make decisions faster than humans and act faster than humans, that might increase the amount of damage that they can cause,” Ghaffari said. “That’s the frontier that hasn’t been explored, and we have to talk about it as we make progress in the future.”

![Mason Ramsey – Twang [Official Music Video] Mason Ramsey – Twang [Official Music Video]](https://i.ytimg.com/vi/xwe8F_AhLY0/maxresdefault.jpg)