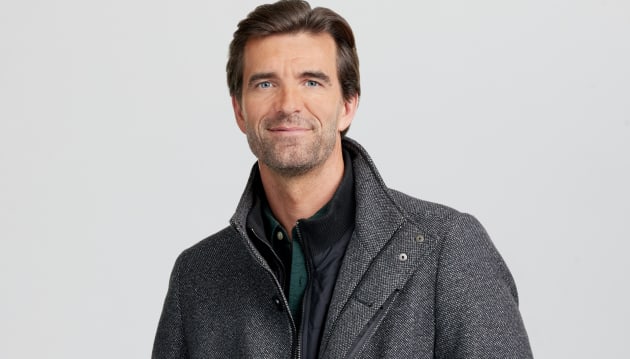

French president Emmanuel Macron sought to turn the page on months of protests over his unpopular plan to raise the retirement age from 62 to 64 on Monday by promising fresh action to improve people’s working lives and salaries.

In a speech on primetime television two days after enacting the new pensions law, Macron said his government, led by prime minister Élisabeth Borne, would work on a series of new measures on law and order, education and health issues to respond to the public anger expressed during the pensions battle.

“No one, especially me, can ignore the demands being made for more social justice and a renewal of our democracy, expressed especially by young people,” he said. “The answer cannot be immobilism or extremism.”

The address was the first step in what will probably be an uphill battle for Macron to repair the damage done to his public image and to his second-term agenda during the battle over pensions reform. But delivering on his promises will be complicated by the fact that his party does not have a parliamentary majority and has struggled to convince opposition lawmakers to back its legislative priorities.

The pensions battle has also left a deep feeling of anger among labour union leaders, who are loath to come back to the negotiating table to discuss the government’s ideas for a new law to improve working conditions and pay, or better professional training for young people to help them fare better in the labour market.

Macron had invited them to a meeting at Elysée palace on Tuesday but they declined, and instead have promised to turn out en masse to a protest set for the traditional Labour Day demonstrations on May 1. Sophie Binet, new head of the hardline CGT union, reacted to Macron’s speech with a quip: “What planet is Emmanuel Macron living on? That speech could have been written by ChatGPT!”

Laurent Berger, who heads the more moderate CFDT union, said the speech was a mere political gambit. “I didn’t hear anything concrete that would calm the anger that workers feel,” he said on BFM TV.

Macron has cast raising the retirement age by two years to 64 as a necessity both to get rid of deficits in the pension system by 2030 and as a symbol that France can thrive in a global economy if it adapts its generous social welfare system.

Opponents of the reform, which also lengthens the time people must work to qualify for a full pension to 43 years from around 40 years now, had argued that other, fairer ways were available to plug the pension system’s deficit, such as by raising taxes on the wealthy or on corporations.

Despite months of negotiating with the conservative Les Republicains party to try to secure their votes, the government ended up resorting to a constitutional tactic known as Article 49.3 to ram though the draft law without a parliamentary vote. It then survived two no-confidence motions filed by the opposition. However, critics criticised the move as heavy-handed and unfair. Street protests and strikes became more unpredictable and violent throughout March, leading to thousands of arrests and injuries among police and protesters.

Once the constitutional court cleared most of the legislation on Friday, Macron signed it almost immediately into law, signalling his firmness even as protesters and opposition parties vowed to fight on. Getting the pensions reform through has been a test of his reformist credentials since he tried to get it done in his first term but was thwarted by the onset of the Covid-19 pandemic.

Macron promised to move on to other issues that were priorities for the public, such as addressing high inflation and the cost of living. He said his government would take stock of progress by July 14, the Bastille Day holiday.

“We have ahead of us 100 days of appeasement, unity, ambition and action for France,” he added.