High unemployment remains a challenge for India, and has been one of the biggest criticisms of Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s government.

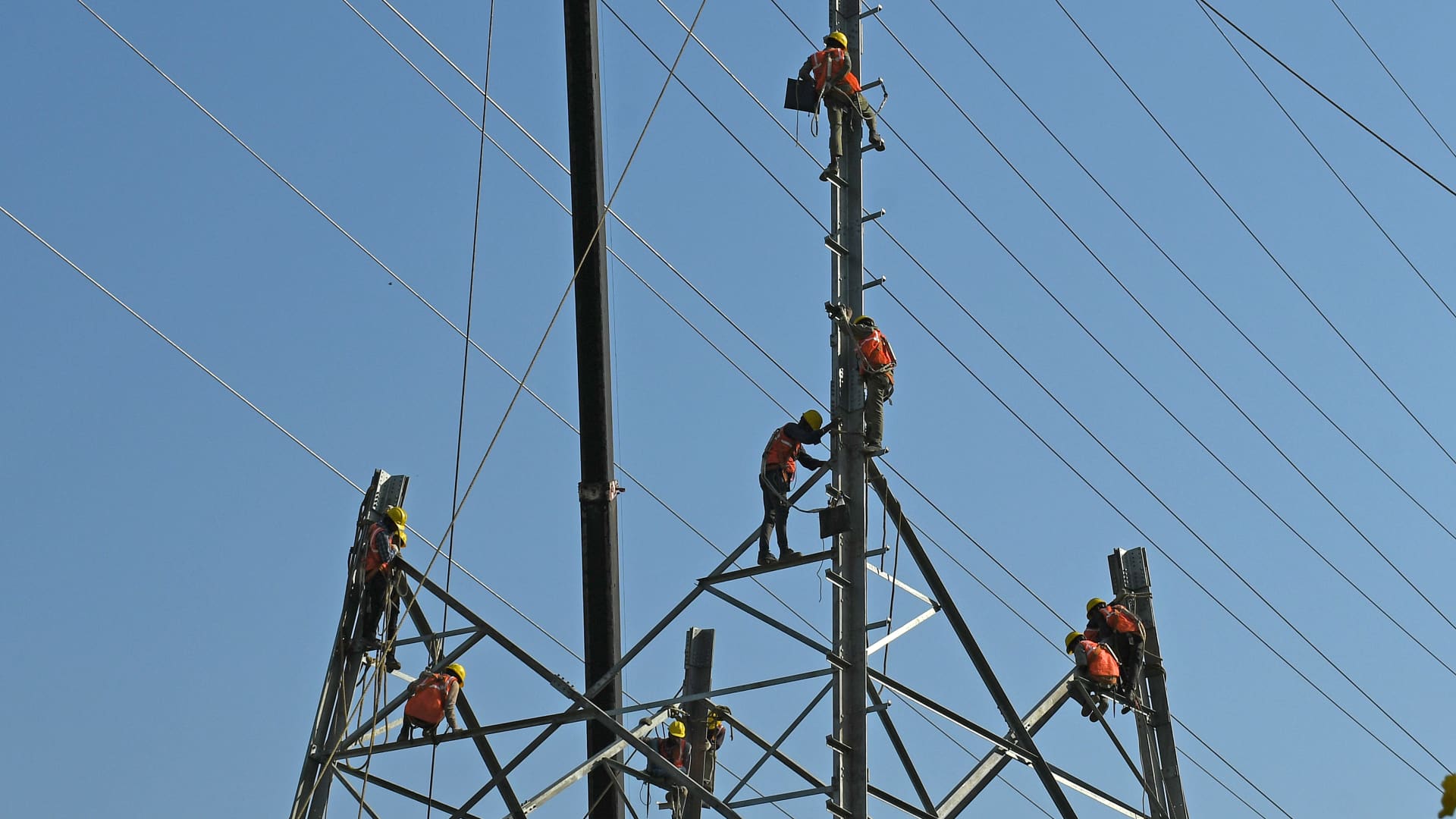

Sopa Images | Lightrocket | Getty Images

India is pumping up its infrastructure spending, a move the government says will create much-needed jobs.

At the annual budget announcement in February, the finance ministry said it will be pumping up capital expenditure by 33% to 10 trillion rupees ($120.96 billion), as India is set to be the world’s fastest growing economy.

However, economists who spoke to CNBC aren’t so optimistic. They say the number of jobs that can be created from a surge in infrastructure investments may be fewer than the government expects.

The government’s focus is “completely wrong” and its policies are “completely against employment generation,” said Arun Kumar, a retired economics professor from New Delhi’s Jawaharlal Nehru University.

“Capex is not the answer, but how the capex is going to be used,” Kumar said, highlighting that not enough money is being pumped into creating “labor intensive” jobs in India.

What’s the problem?

Employment in India is divided into different sectors: organized and unorganized.

Businesses in the organized sector are often licensed by the government and pay taxes. Employees are usually full-time staff and have a consistent monthly salary. Companies in the unorganized sector are usually not registered with the government and employees work ad hoc hours with irregular salaries.

When people in India are “too poor not to work,” they’ll result in doing “residual work” with very low incomes such as driving rickshaws, carrying luggage, or even selling vegetables on the street, Kumar said.

According to Kumar, the organized sector only makes up 6% of India’s workforce. On the other hand, 94% of jobs are in the unorganized sector — with half the jobs in agriculture.

As India’s infrastructure sector becomes more reliant on technology and automation, the upcoming boom in projects will create jobs for the organized sector, Kumar said. A lack of investments in the unorganized sector hence leaves many stuck with unstable jobs without a fixed income.

Those employed in agriculture are also “stuck” with low salaries since inadequate investments leave little room for them to upskill, Kumar said.

High unemployment remains a challenge for India, and has been one of the biggest criticisms against the government of Prime Minister Narendra Modi.

According to the Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy, an independent think tank, unemployment rose to a 16-month high at 8.3% in December 2022, but dipped to 7.14% in January.

CNBC reached out to the Ministry of Finance and is waiting for a response.

A more technologically advanced infrastructure sector also means fewer jobs will be available for those in the organized sector, Chandrasekhar Sripada, professor of organizational behavior at the Indian School of Business said.

“New generation manufacturing is not labor intensive. The number of jobs it can create at the unit-level will not be as high as it used to be,” Sripada said. “In the 1950s, if we set up a steel plant, we would employ 50,000 people. But today … we will employ 5,000 people.”

Who’s most affected?

Sentiment in India’s job market remains weaker than some countries in the region as a result of a mismatch of skills.

India’s labor force participation rate — or the number of active workers and people looking for jobs — came in at 46% in 2021, according to data from the World Bank. That’s lower than some other developing nations in Asia, such as 57% for Bangladesh and China at 68% in the same year.

Female work participation rate also dropped from 26% in 2005 to 19% in 2021, data from the World Bank showed.

“We’ve seen a very unexplainable drop in the participation of women in the labor force during Covid,” Sripada said. “The caregiving responsibilities on women just increased far more and many dropped out of the workforce, and probably that hangover is continuing.”

Even youth with college degrees are struggling to find jobs.

Youth unemployment, or those in the workforce between 15 to 24 years old with no jobs, stood at 28.26% in 2021 — that’s a 8.6% higher than 2011.

Many of the youth living in rural areas are “semi-educated” because they have degrees in their hands but are not skilled enough to gain employment, Sripada said. It’s also a challenge for employers to create jobs that target these people, he added.

“We have enough colleges to provide bachelor degrees, but these degrees … do not prepare them with enough skills to get employment,” he said.

![Mason Ramsey – Twang [Official Music Video] Mason Ramsey – Twang [Official Music Video]](https://i.ytimg.com/vi/xwe8F_AhLY0/maxresdefault.jpg)