This is part of a series, ‘Economists Exchange’, featuring conversations between top FT commentators and leading economists

The Federal Reserve has officially embarked on its first campaign to ease monetary policy since Covid swept across the globe in 2020 and triggered the worst economic contraction since the Great Depression.

Last month, the US central bank opted to go big, delivering a larger-than-usual half-point cut that lowered the benchmark policy rate to 4.75-5 per cent. In the past, such aggressive moves from the Fed have typically been responses to economic or financial calamity. But today’s backdrop is particularly benign. The US jobs market is healthy, consumers are still spending and growth on the whole is solid, while inflation has dropped dramatically from its 2022 peak and is now within range of the Fed’s 2 per cent target.

Some price pressures still percolate — especially across the services sector — and there are lingering concerns that the economy will eventually run out of steam, but recession alarm bells that loudly blared in recent years have quietened. John Williams, president of the New York Fed, intends to keep it that way as he and his colleagues plot out the next phase of interest rate decisions in their march to a “neutral” policy setting that no longer dampens demand.

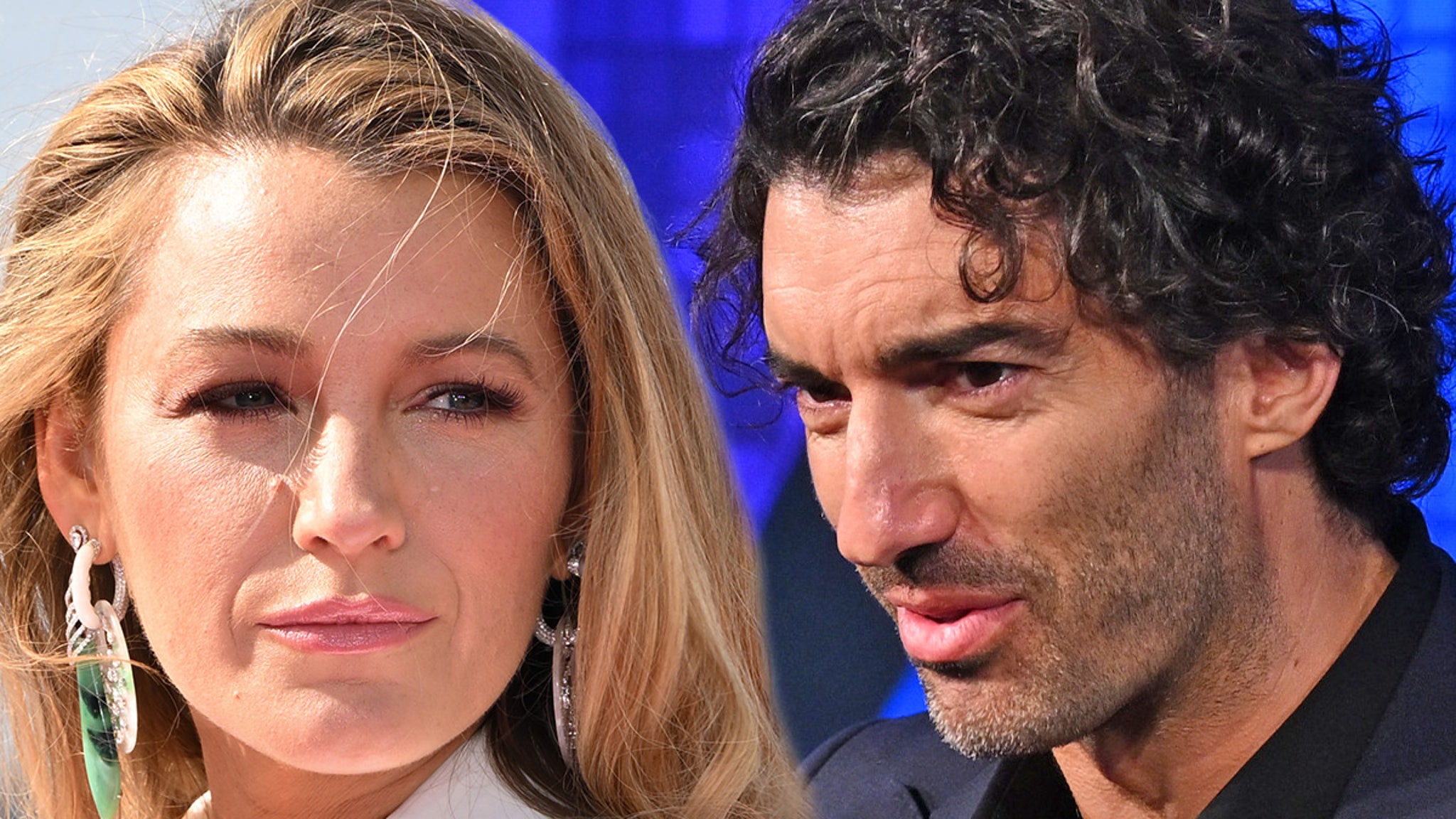

A permanent voting member on the Federal Open Market Committee and a close ally of chair Jay Powell, Williams shares with the Financial Times his views on monetary policy, his prognosis for the labour market and what inflation surprises still keep him on edge.

Colby Smith: I’d like to start with the labour market because the September jobs report was quite something. What were your biggest takeaways?

John Williams: This was a very good report. Unemployment is around 4 per cent, we’re seeing very good job growth, and I think it is consistent with what we’ve been seeing with some other indicators, like spending and gross domestic product [GDP] numbers. This is an economy that’s continuing to grow. The labour market is in a very good place.

Also, it is consistent with the other message, which is we have seen a general cooling of the labour market relative to where it was a couple years ago when all the indicators were [saying], “this was the hottest labour market in generations”. We’ve seen across a broad set of measures — whether quits or vacancies or all the other indicators we look at, including the unemployment rate — that this is a labour market that is solid but is very much in balance. I saw the report as positive in that way.

CS: It followed several months of much softer data and much slower monthly growth. To what do you attribute that weakness we saw over the summer? Was it seasonal factors or weather related?

JW: I don’t want to over-emphasise any specific month of data, whether it was, as you mentioned, some of the softer readings we saw in previous months, or, this reading, which was very good.

You want to look at this in the totality of the data, looking at multi-month averages of job growth, looking at what’s happening in other indicators. A number of factors can cause the data to move up and down over a short period of time . . .

I think the labour market is in balance, and I’m watching the data to tell us where it’s likely to go going forward.

You look at the data before this latest report, clearly the job growth was definitely softer than what you would think would be the normal number of job growth to keep the unemployment rate constant. I think the latest data may be a little bit more encouraging on that. That said, I’m very focused on making sure we achieve our maximum employment and price stability goals.

CS: Is it your expectation that the pace we saw in September is probably not going to continue going forward? And on the point about the break-even rate for monthly employment, how has your thinking changed?

JW: Any specific month is going to have some random variation for various reasons, and it could be some seasonal factors or other factors.

In terms of the break-even [rate], I think this is really hard. It was really hard before the pandemic to know exactly what that is, because we’re trying to figure out what’s the growth of the labour supply translated into what a payroll number is.

But we also have a number of factors that are complicating that calculation. One is we’ve definitely seen very strong labour force growth over the last past two years, in part because of immigration and people joining the labour force. The other is that there’s the issue of revisions based on collecting more data from various surveys and sources.

I probably don’t put a lot of weight on trying to understand “is the number 100,000 or 200,000 on an adjusted basis?”, because I think there’s just a lot of uncertainty about that.

I do look at the broader set of indicators to tell me, is the labour market tight? Is it loose? Which way is it moving? Therefore you do want to look at things like quits and vacancies and these other things, which probably give a better read of what’s happening in terms the state of the labour market.

CS: On your point about immigration and the labour force increasing here, that’s been cited repeatedly to explain why we were seeing the unemployment rate increase. How significant of a factor do you really think that is? And are there further grounds for expecting labour supply to improve from here?

JW: I think that it’s hard to know, because these are things that people have to estimate based on different sources. My reading of the evidence is that we’re still in the midst of getting significant, strong labour supply growth from immigration. That’s probably going to taper a bit relative to what we saw last year and in the first part of this year, but it’s still a positive.

How do we understand that GDP grew 3.2 per cent last year and it’s growing 2.25 per cent or better this year and yet we’ve seen the unemployment rate come up and we’ve seen this broader cooling of the labour market?

The only way I can understand this — because I only know two words, supply and demand — is supply has clearly been very strong over the last two years. Labour force growth is part of that supply story and productivity growth is the second part of that.

At least in the near term, the supply side growth rate of our economy has been above 3 per cent over these two years. I don’t think that’s a long-run number, but that’s what it is now.

What it is in the future will depend on how productivity and the labour force evolve over time. A big part of the story last year — less so now — is labour force participation. We saw a big decline in labour force participation with the pandemic and after that, and we’ve seen a return of participation.

I don’t expect it to continue to rise that much in the future, but it is one of the reasons we’ve seen the supply side of our economy bounce back so strongly since the pandemic.

CS: Do you still harbour concerns about inflation?

JW: Well, I’m always focused on achieving our price stability goal and getting inflation back to 2 per cent on a sustained basis. That’s definitely very much a priority, along with maximum employment.

And we’re not there yet. The inflation data have been very encouraging. Overall personal consumption expenditures (PCE) inflation is now around 2.25 per cent. That’s a big improvement from the over 7 per cent we saw back in summer of 2022, but underlying measures of inflation are probably still in the 2.25-2.75 per cent range, depending on which measure you look at. So we still have a ways to go to get inflation down to 2 per cent on a sustained basis.

I feel like the trajectory of the data is supporting my view of [having] greater confidence that we’re moving towards 2 per cent inflation on a sustained basis. But, the inflation data surprised us in the past, and we have to make sure we get there.

The current stance of monetary policy is really well positioned to both hopefully keep maintaining the strength that we have in the economy and the labour market, but also continuing to see that inflation comes back to 2 per cent.

My own forecast is that PCE inflation will be close to 2 per cent next year.

CS: How worried are you about the ongoing conflict in the Middle East and the potential impact on oil prices and in turn inflation?

JW: We live in a global economy and a global financial system, and geopolitical events around the world clearly can have an impact. One of the channels this often happens is through commodity prices, or in this case specifically, energy prices.

So far, we haven’t seen a dramatic increase. We’ve definitely seen increases in oil prices, but it’s definitely on my list of risks to the global economy and to inflation in the near term.

There are a lot of uncertainties when you think about the US economy beyond that, and I think this is one of those cases where you track the evolution of the data and what it implies for the outlook and some of the risks.

The risks to the inflation outlook, from my perspective, are pretty balanced. There are reasons inflation could come down more slowly than I expect, but also reasons it could come down more quickly.

CS: One factor that has been keeping inflation higher is related to housing. Why haven’t we seen a substantive downshift there and when do you expect that to happen?

JW: On the other categories of inflation, goods inflation has clearly come way down. It’s now down to the levels we saw before the pandemic, and I expect that to continue. Core services excluding shelter has been coming down steadily, so we are not seeing any signs of that inflation getting sticky.

One of the reasons that inflation is coming down the way it has is we’ve seen the economy get back in balance and the labour market get back in balance.

This one category — housing — has been more sluggish to come down. We’ve looked a lot at the data on the rents that are implied by newly signed leases, and that inflation rate came down to pre-pandemic rates some time ago. Based on the pre-pandemic experience, one would have expected that to filter directly into the official statistics in an almost mechanical way. That hasn’t happened in the way that I and some expected.

It’s hard to know [why] given the extremely unusual circumstances we’ve been dealing with the last few years. One is that demand for housing rose dramatically following the pandemic . . . and part of it is probably more permanent. There’s just more demand for space for people who used to work in offices and now work in a hybrid or fully remote environment.

The second is that the movement in rents was just very large in the early post-pandemic period, and so there’s likely to be a catch-up effect, which we have seen in other categories, meaning that if you moved, your rents probably went up quite a bit and that got captured in the official data. For those people who didn’t move, they probably didn’t get full mark-to-market on rents and it is just taking longer for that process to adjust.

It’s hard to know how big that effect is and how long it will last. Some indicators suggest that’s probably played out by now, and we should see more of a translation of the rents of newly signed leases into the inflation data . . .

The direction of this is going in the right way. All the current indicators are that shelter inflation should be coming down. It’s going to be coming down, clearly more slowly than I had earlier anticipated.

From a policy perspective, this is inflation and we want 2 per cent inflation, so I’m not excluding shelter from my thinking about what inflation is, but it is probably in a way echo effects of past events. It doesn’t reflect the tightness of the market or the imbalance in the economy in terms of inflation rates going forward . . . Forward-looking indicators are moving closer to our target.

CS: Is there any sense that in this post-pandemic period, the economy is perhaps just less sensitive to changes in interest rates?

JW: There’s always uncertainty about the effects of monetary policy actions on the economy, because monetary policy responds to the economy and the economy responds to monetary policy. It’s very hard to discern cause and effect . . .

That same uncertainty applies as it did before. I think monetary policy is clearly working in the way we intended, and I think you see it in the response of financial conditions to policy actions and communications.

Going back a few years, as we have brought monetary policy from being accommodative or supporting growth to more neutral and then to restrictive, meaning slowing growth, we’ve seen the economy move from being extraordinarily strong to one where demand and supply are back in balance.

One area that I would highlight that is hard to quantify but probably means monetary policy is having somewhat less effect than it has on average, is that there were a lot of people, households, families and businesses who refinanced at very low rates during the pandemic. This is the “lock-in” effect we hear about. So, if you had a mortgage at a very low rate, you’re probably reluctant to move because if you sell your house, you lose the financial value of that low interest rate mortgage.

That seems to have slowed the activity of people moving and selling their houses. Businesses, too, were able to lock in low interest rates for their borrowing for their business needs. That’s not a permanent effect. Eventually, those loans or mortgages will roll off, or people will move for other reasons. But arguably, as we’ve raised interest rates, the direct effect on some people has been not so great.

CS: On the more immediate decisions that you all are confronting here, in light of the latest jobs report, was a 50 basis point cut in September needed?

JW: When I think about the question of what’s the appropriate setting for monetary policy, I naturally go back to our two goals of maximum employment and price stability, or 2 per cent inflation.

We’ve definitely seen the imbalances in the economy and the labour market — meaning demand exceeded supply — coming back towards balance and now are in balance. That is a process that has taken a few years and has continued through the first nine months of this year.

Late last year, the inflation data were looking very favourable, everyone was expecting us to cut rates quite a bit this year, but then we got some significantly higher readings. That, appropriately in my view, called for us to be cautious and really analyse and assess that data and get that greater confidence in inflation moving toward 2 per cent on a sustained basis.

So coming to the September meeting, from my perspective, it was not just the labour market data that were important. The other part was what’s been happening on inflation.

We had put in a very restrictive stance of monetary policy in my view, we had kept it at a very restrictive stance all the way until the September meeting in order to make sure that we’re getting inflation on track to get back to 2 per cent on a sustained basis.

Once we had that data — and I found it pretty compelling that inflation was on track and we’re seeing the labour market get into balance, which means we’re not going to get additional inflationary pressures from the tight labour market — then looking at the stance of monetary policy, it made sense, as the chair said, to recalibrate policy to a place that is still restrictive and is still putting downward pressure on inflation, but significantly less so.

The decision was right in September and it would be right today, because for me, it wasn’t about one or two labour reports or other pieces of data. It was really about the totality of what we’re seeing.

It’s important to remind ourselves that if you look at other data that we had at the September meeting, GDP growth in the first half of the year was solid, consumer spending data have been good. There were a lot of indicators that are broadly consistent with what we’ve seen in the latest employment report.

I strongly supported the action we took, and I think it was the right one.

CS: But if additional labour market softening is not needed to feel confident about inflation going back to target, why is restrictive policy necessary at all?

JW: Inflation is still running above the target. Some of the measures of underlying inflation, whether you look at core or other ones, are still above 2 per cent and probably average around 2.5 per cent if you look at different measures. So, we still have a way to go to fully get back to 2 per cent on a sustained basis.

Even though we can talk about how restrictive policy is and that can become a very philosophical debate, the key thing is that the economy is continuing to grow, and we’re still adding a good number of jobs.

I don’t want to see the economy weaken. I want to maintain the strength that we see in the economy and in the labour market.

I think the recalibration of policy sets us up really nicely to achieve both of those goals — inflation moving back to 2 per cent and still the economy growing.

As you saw in the economic projections that my colleagues and I put out, I do expect on the baseline view of my forecast that we will be moving monetary policy to a more neutral setting over time. That is an important ingredient in why the economy will not only continue to grow and hopefully maintain the strength that we’ve seen, but also is consistent with inflation coming back to 2 per cent.

CS: So just based on Fed officials’ latest projections, Chair Powell signalled that the baseline was two more quarter-point cuts for the remainder of the year. Is that what you support?

JW: We’ll get more data between now and the next meeting, and I think the important thing is, every meeting, we will make the decision [based on] what is appropriate at that time.

My general view is that if you look at the median of the Summary of Economic Predictions (SEP) that was put out last meeting, that is a pretty reasonable representation of a base case. Of course, the economy rarely follows a base case. There’s a lot of uncertainty in the economy out there. I personally expect that it will be appropriate again to bring interest rates down over time.

Data dependence has served us extremely well . . . Right now, I think monetary policy is well positioned for the outlook, and if you look at the SEP projections that capture the totality of the views, it’s a very good base case with an economy that’s continuing to grow and inflation coming back to 2 per cent.

CS: It doesn’t sound like you see much urgency to continue moving in these big 50 basis point increments.

JW: The move in September was really one of having kept a very restrictive stance of policy to ensure that inflation really is on its way back to 2 per cent. We had to think hard about making sure that [inflation data earlier this year] wasn’t just an anomaly. Given that we were very careful in keeping the stance of policy restrictive, it made sense to do that recalibration, but I don’t see that as the rule of how we act in the future.

CS: In terms of the various scenarios that you’re thinking about, what are the circumstances in which you would consider a pause in interest rate cuts? What would motivate you think about doing a half-point cut again?

JW: The way I think about it really goes back to what are the data telling us about where the economy is, our assessment of that, what’s the economic outlook and what are the balance of risks?

When you consider a situation where we see inflation coming back more quickly to 2 per cent on a sustained basis — not just a good reading or two — that then obviously that would call for policy to normalise a little bit more quickly. Similarly, if inflation takes a little longer to come down, that would call for interest rates to come down more slowly.

The big question that’s out there is, where do we end with interest rates? The answer to that question is the same as my answer to, how quickly are we going to lower rates?

It’s going to depend on what’s happening with the economy, the labour market and inflation. We can theorise about what the neutral interest rate is, we can write down models, and I spend much of my life doing that. But the test of this isn’t the theory or even the models. It’s really about, how does the economy in 2025 and 2026 evolve, and what interest rates will best achieve our goals?

The data and all the information we get will be very informative on that, just as it has been in the past . . .

As we progress over the next year or two in normalising interest rates, then we’ll also get a cleaner idea — at least under those circumstances — of what interest rate will best keep us at 2 per cent inflation once we’re there, and keep this economy strong and in a good balance.

CS: Are you of the view, though, that the short-run neutral rate has likely risen compared to pre-pandemic levels?

JW: I honestly do not find the concept of a short-run neutral rate useful, and it’s not because it’s illogical, but because when I think about the economy over the next couple of years, there are so many factors that are influencing supply and demand. We talked about the labour force, immigration, all the post-pandemic catch-up effects and what we’re seeing in the global economy . . .

When we think about making monetary policy, we say this over and over, but it’s really an assessment of where you think the economy is today, where it’s likely to be going over the next couple years, and then what are the balance of risks around that? That’s a very different kind of question than the abstract question of, once you accomplish all that, and the economy is in a nice, steady state — balanced growth and low inflation — what interest rate do you expect to prevail?

Do I think that right now, there are factors that probably argue for higher interest rates than neutral? Well, one is inflation is still higher than 2 per cent and that argues for somewhat higher interest rates than you would have in the long run when inflation is 2 per cent.

The other — and this is hard to know — but it seems like there is still some tailwind from some of the fiscal support from the pandemic affecting the economy. There may be other factors that in the short run are boosting demand relative to supply, but of course we have factors boosting supply as well.

CS: If there is uncertainty, though, about where the level of interest rates is to reach this equilibrium level, does that not then favour a more gradual approach? Do you not risk overshooting?

JW: If what you mean by gradual is do the Bayesian process of getting more data, updating that data and reassessing what you are seeing in the economy and what it is telling you policy needs to be to achieve the goals because of this uncertainty, than that is absolutely right. It is not gradual in the sense of “I am intentionally just waiting a period of time to make a decision.” . . . What I don’t think is the right way to think about it right now is how it’s ended up being understood because of past use of the word “gradual” with Fed policy, which is it tends to be seen as almost a mechanical move — whether it’s every meeting, every other meeting or a specific calendar-based view . . .

We’re not on a preset course of policy. We’re on a learning course for policy. And that’s also why I personally don’t see us trying to follow some kind of very specific pattern.

CS: The Fed, of course, is an independent, apolitical organisation. But in this US presidential election, the two candidates have proposed very different economic platforms. How are you incorporating those differences into your thinking about the economic outlook?

JW: I’m not going to comment on anything political or anything about the campaigns . . . When we get to the point where Congress or the administration actually passes legislation, obviously we’ll want to analyse all that. But right now, I’m just focused on getting our job done with what we’ve seen in the economy and doing our very best to achieve that.

The above transcript has been edited for brevity and clarity