Unlock the Editor’s Digest for free

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

More than three-quarters of the foreign money that flowed into China’s stock market in the first seven months of the year has left, with global investors dumping more than $25bn worth of shares despite Beijing’s efforts to restore confidence in the world’s second-largest economy.

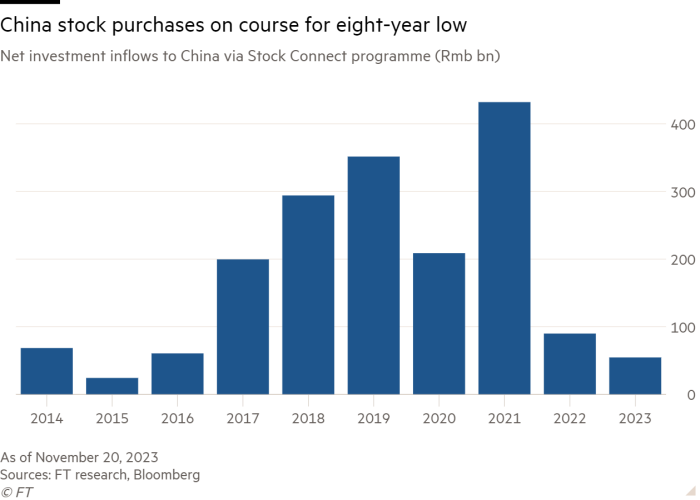

The sharp selling in recent months puts net purchases by offshore investors on course for the smallest annual total since 2015, the first full year of the Stock Connect programme that links up markets in Hong Kong and mainland China.

Traders and analysts said a lack of forceful policy support from Chinese leaders had convinced global institutional investors to hold off on buying until growth rebounded enough to make China’s market competitive with others in the region.

“Japan’s on fire, India, Korea, Taiwan — that’s the problem,” said the head of one investment bank trading desk in Hong Kong. “Right now the thinking is, ‘I don’t need to be in China, and if I am, it’s holding my portfolio back.’”

Global investors began 2023 buying Chinese stocks at a record pace in January, anticipating an economic rebound as the country abandoned its disruptive “zero-Covid” regime.

But foreign funds have forcefully sold down their positions in recent months in response to mounting concerns over a liquidity crisis in the property sector and disappointing growth readings.

Since touching a peak of Rmb235bn ($32.6bn) in early August on government pledges to provide more substantial economic policy support, net foreign inflows to China’s stock market this year have tumbled 77 per cent to just Rmb54.7bn, according to Financial Times calculations based on data from Hong Kong’s Stock Connect.

Bruce Pang, chief economist for greater China at JLL, a real estate research and investment company, said Chinese authorities’ subsequent pledges to provide more support for struggling private property developers had hit market sentiment.

“They’ve made similar pledges every quarter this year,” Pang said, “but the latest housing price data shows there’s still more policy support needed to generate a sustainable recovery for the property sector.”

Foreign selling of Chinese shares has helped push the CSI 300 index of Shanghai- and Shenzhen-listed stocks down more than 11 per cent in dollar terms this year, compared with gains of 8 to 10 per cent for equity benchmarks in Japan, South Korea and India.

Financial institutions have instead favoured markets in India and South Korea this year with net inflows of $12.3bn and $6.4bn, respectively, according to estimates from Goldman Sachs. Global buying of Korean stocks has put Seoul on track for the first year of net foreign inflows since 2019.

While equity strategists at Wall Street’s biggest investment banks have tipped China’s stock market to fare better in 2024, expectations for the size of those gains vary substantially.

Analysts at Goldman Sachs recently forecast the CSI 300 to end next year up about 17 per cent from its current level on the back of higher earnings and rising valuations for Chinese companies.

Morgan Stanley strategists have pencilled in gains of 7.5 per cent during the next 12 months for Chinese equities but warned that “we cannot rule out further allocation reduction and structural shift of investment away from China” if policymakers did not move to more actively support growth.

“What convinces a portfolio manager running an $1bn fund to put 10 per cent of that back into China?” said the trading desk head in Hong Kong. “The answer is decent upside long-term growth numbers — if you can’t get that, investors won’t go there.”

![Mason Ramsey – Twang [Official Music Video] Mason Ramsey – Twang [Official Music Video]](https://i.ytimg.com/vi/xwe8F_AhLY0/maxresdefault.jpg)

.jpg)