Asset managers scrambling to boost assets and enter new markets while keeping costs down are turning to partnerships that split responsibility for sales and clients from the actual investing.

Enthusiasm for so-called “subadvisory” contracts is especially high among European money managers looking to break into the US market and institutional managers hoping to tap individual investors. That is because the arrangement allows them to tap the US retail market without having to invest in huge sales forces.

Asset managers on both sides of the Atlantic that have historically offered mutual funds are also entering similar deals as a way of extending their investment strategies in fast-growing sectors such as exchange traded funds or separately managed accounts.

In a subadvisory relationship, the main fund manager owns the fund and takes responsibility for gathering and handling customer money. The subadvisor is responsible for investment decisions: how that money is put to work.

“The most effective subadvisory set-ups are almost like a strategic partnership. You’re effectively renting distribution,” said Ju-Hon Kwek, the senior partner who leads McKinsey’s North American asset management practice.

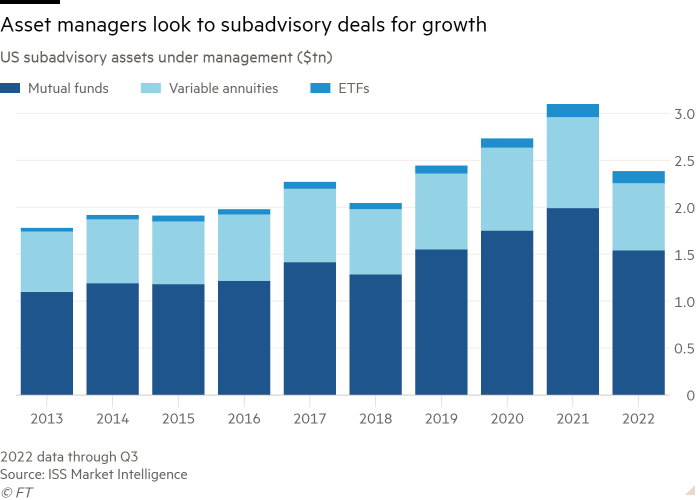

Total US assets in subadvised funds where unrelated asset managers share the management fees nearly doubled between 2013 and 2021 to $3.1tn before falling back in 2022 along with the broader bond and equity markets to $2.4tn, according to the data provider ISS Market Intelligence. Growth has been particularly rapid in ETFs, where assets have more than tripled.

For Scottish fund manager Baillie Gifford, its first 2003 subadvisory contract with fund giant Vanguard proved transformational. Global subadvisory assets under management have nearly tripled since 2012 to $64bn, and such arrangements now account for a quarter of the group’s total AUM and half of its North American business.

“Our partnership with them was a real accelerant of our North American business. It was almost a seal of approval,” said partner Nick Jones. “You are getting access to a much larger market and not having to bear some of the costs.”

Most fund managers do not disclose how fees are split, but ISS MI’s Carl Robinson estimates that for a fund with a 60 to 70 basis point management fee, the subadvisor will receive 30bp or less.

UK fund manager Schroders first turned to subadvisory deals in 2016 when it entered into an arrangement with Hartford to do the investing for $3bn in assets.

“We decided to outsource our mutual fund business because we weren’t really getting traction and we didn’t have a big enough sales team,” says Phil Middleton, chief executive of North America for Schroders, which now serves as the subadvisor for 52 funds with $46.7bn in assets.

Large distribution houses such as Vanguard and Hartford tend to cut deals with two kinds of subadvisors: those with strong brands that become part of the fund name and those that specialise in a particular area of investing that the larger firms do not have in-house.

“You get the benefit of M&A without actually doing a transaction,” says James Thomas, a partner at Ropes & Gray

The fund platforms spend long periods considering a manager’s record, governance and performance before agreeing to do a deal. “This is a very long cycle of getting to know you and a courtship process. It’s very important to both sides to get it right,” says Jared Buell, head of intermediary distribution for North America at Vontobel Asset Management. The Swiss group has US subadvisory arrangements with Virtus and American Beacon and is seeking to expand.

When Vanguard added Ariel Investments as a subadvisor to its existing Explorer Value fund earlier in 2022, the appointment came after years of cultivating the larger fund house. Ariel, one of the US’s largest minority owned investment firms with $14.6bn AUM, hopes that the arrangement will help the firm persuade many more companies to include an Ariel option in their employee retirement plans.

“In these days when we are trying to get more Americans to participate in retirement [savings], to be able to link into our story and our performance [means] there’s an excitement that would not otherwise exist,” said Malik Murray, Ariel’s head of business development.

Vanguard has been using subadvisors for five decades, and it monitors the relationship closely. It has recently started using a variable fee structure that rewards subadvisors for beating their benchmarks and penalises them for falling short over a three to five-year period.

Long-term performance matters, but so do other factors such as the fund staying focused on its particular speciality, said Dan Reyes, global head of the portfolio review department. “We look for style drift and where they are getting their ideas from,” he said.

As falling markets hit AUM and therefore fees, more asset managers are likely to find subadvisory deals attractive because they allow each side to expand without a massive financial investment and the combinations create economies of scale, says Stephen Erni, a partner at the Bain consultancy: “The open architecture of the system is really the wave of the future.”

![Mason Ramsey – Twang [Official Music Video] Mason Ramsey – Twang [Official Music Video]](https://i.ytimg.com/vi/xwe8F_AhLY0/maxresdefault.jpg)