Like an Antony Gormley installation on an epic scale, on the northern tip of Denmark people gather in their hundreds to walk out into the sea. Not any old bit of sea though, for this is Grenen, where the waves of the Skagerrak strait and Kattegat sea collide across a sand spit tapering far out into the dark waters. Swimming in these wild currents is strictly forbidden.

Grenen, meaning “the branch”, is the final outstretched finger of Skagen Odde, The Skaw in English, a 25km-long peninsula of shifting sands, lighthouses, half-buried churches, vast skies and herrings. In an era of global warming, could its white sands soon be giving the Med a run for its money?

Skagen Odde has long been beloved of artists — drawn by the “blue hour” when sea and sky form an opalescent continuum — and well-heeled folk from Copenhagen, turning up in Range Rovers to visit their summer homes. “It’s our Cape Cod,” says a Danish friend. But many other Europeans wouldn’t have the foggiest.

Its remoteness is its appeal. It took my wife Gabrielle and me about two-and-a-half hours to drive from the nearest significant airport, at Aarhus, crossing a pancake-flat landscape of fields and forests, as we sought a detox short break from British politics.

You would think that going once would be enough. But tourists are drawn back to Skagen Odde again and again to experience something elemental, just as every night they gather to watch the sunset, applauding as the red disc slides below the horizon, colouring the sky scarlet.

The landscape here is on the move. Migrating sand dunes constantly redraw the map in these parts, even obliterating settlements. Residents used to have to dig out the entrance to the 14th-century St Laurence’s church before every service. Around 1795 they gave up and abandoned it — today only the tower remains, its base buried in the sand. It makes a popular destination for walk or bike ride from Skagen, the peninsula’s main town.

With its yellow-painted gingerbread houses and picket fences, Skagen is Denmark’s most northerly town and is embedded in the national psyche. It become famous from the end of the 19th century after it was adopted by a colony of artists, drawn by the simple lifestyle and the region’s astonishing light.

Today, their work can be seen at the Skagens Museum, which also gives a glimpse of the lives of fishermen and farmers here at the turn of the century. Visitors can stay a few steps away at the Brondums Hotel, where artists such as Michael and Anna Ancher and PS Krøyer slept, ate and drank, donating works to help cover their bills.

There are obvious parallels here with other fishing villages adopted by artists at around the same time — think St Ives or Collioure — but Skagen has a dual identity, which may or may not add to its appeal, depending on your tastes. Because alongside the half-timbered cottages is a serious fishing port.

The town’s charming lanes and fin de siècle hotels do not offer views of boats bobbing in a small harbour; the whole seafront is dominated by a massive port and odoriferous fish processing plant, with vast trawlers bringing in catches from some of the world’s most dangerous waters.

But the fish is certainly fresh. Skagen Fiskerestaurant, down at the port, serves up lobster rolls, oysters and local craft beer, while up the coast at Skagen’s grey lighthouse is the atmospheric Blink, serving great fish, a remarkable range of vegetables and wide vistas.

To get to the beaches and the spit at Grenen you need to head slightly out of town either on foot or — much more likely — by bicycle. Skagen is designed for cycling: flat and clearly marked bike routes take you out to the migrating dunes or to Gammel Skagen (Old Skagen), a former fishing community that now offers some upmarket hotels, summerhouses and remarkable sunsets.

There is plenty to occupy you in Skagen, from galleries and boutiques to quaint tea shops and bakeries with spectacular pastries. And one can also witness the Danish practice, which never ceases to amaze people visiting from elsewhere: parking a sleeping child in a pram outside a café (sometimes out of sight) while the parents tuck into a meal inside.

On your way to Skagen, make sure to stop off at Aalborg, the biggest city in northern Jutland and now firmly established as a leading cultural centre with a sparkling waterfront. Residents of the industrial town claim in surveys to be among the happiest in Europe.

The only question is when to go. The tourist authorities market the region as the perfect place for some Danish winter hygge, when snow lies on the beaches and the sands of Grenen feel like the end of the world.

The summer is the obvious answer, although Skagen gets busy in July, especially around the notorious “Week 29”, which is spoken about in reverential tones as the week when Denmark descends upon the town to party.

We went in September as the nights started to draw in, with the Copenhagen elite back at their desks. But the idea of holiday crowds is relative in this part of the world. The beaches of Skagen are never likely to be confused with the Costa del Sol — at least not yet.

George Parker is the FT’s political editor

For more information on visiting the area, see enjoynordjylland.dk. Brondums Hotel (broendums-hotel.dk) has doubles from about DKK1,230 (£140)

How to rent your own Danish summerhouse

Retreating to a rustic summerhouse has long been part of the Scandinavian tradition, an annual celebration of friluftsliv (outdoor living). Cabins are passed down between generations and often used by extended families, but most have traditionally remained beyond the reach of foreign visitors. That is now changing, in part thanks to a young company based in Aarhus and founded by seven former Airbnb employees, which has managed to encourage private owners to rent out their summerhouses for the first time.

“On average these summerhouses were standing empty for 300 days of the year, so there was this huge untapped resource,” says Cathrine Reimann, one of the founders of Landfolk.

The company was created in early 2021, and by June that year it had 100 houses on its books. With new investment it grew rapidly, expanding to Norway, Sweden and Germany. Today it offers about 2,500 properties, 1,500 of them in Denmark; 70 per cent of the houses had not previously been let. Unlike Airbnb, owners must apply to have their property assessed for possible inclusion; Reimann says about half of applicants are rejected.

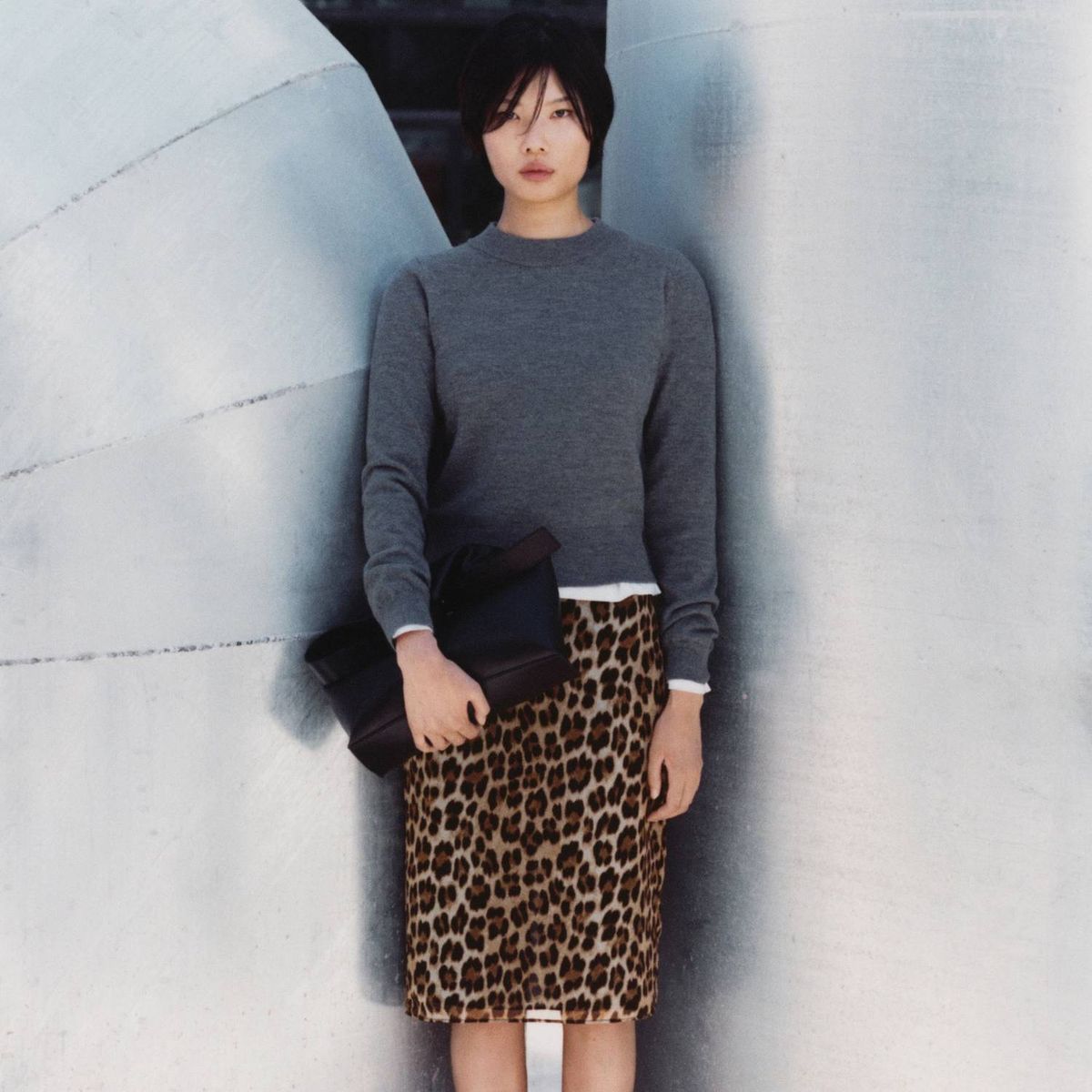

On Skagen Odde, about 30 summerhouses are currently available through Landfolk. They include Hamilton House (pictured above), a black-and-white-painted wooden cottage with thatched roof and flagpole, set among the dunes to the north-west of Skagen. Built by a Swedish count in 1929, it sleeps eight and has a large terrace from which to watch the sunset (from about €3,300 for five nights, including cleaning and heating). Alternatively, there’s a newly built architect-designed cabin (pictured below) in Kandestederne, with blonde-wood walls, a sedum roof, wood-burning stove and outdoor hot tub and shower (sleeps up to 10, from €2,058 for five nights). landfolk.com

Find out about our latest stories first — follow FT Weekend on Instagram and X, and subscribe to our podcast Life & Art wherever you listen