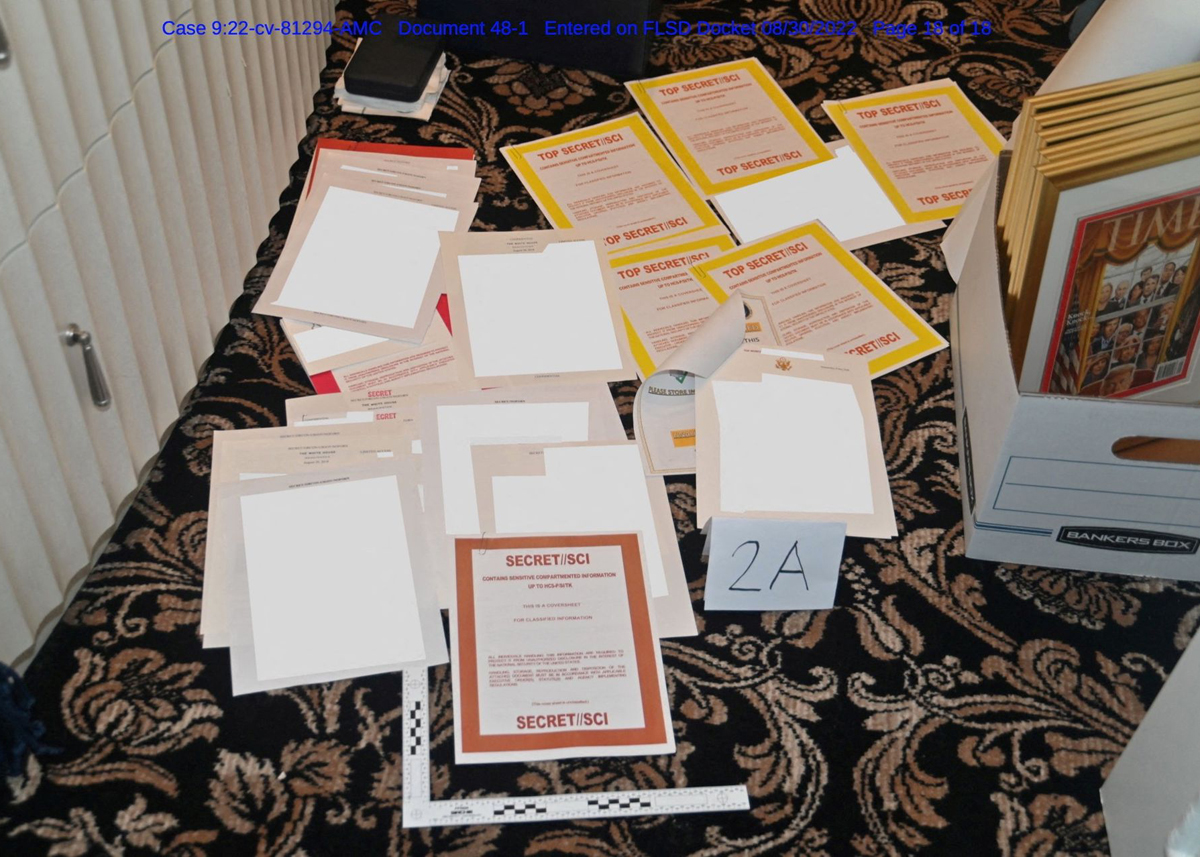

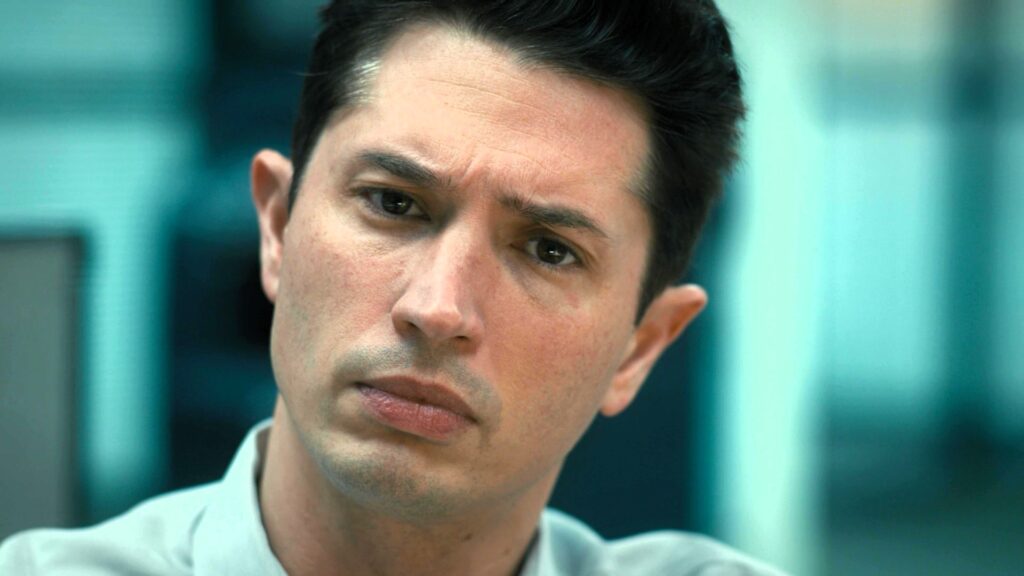

A photo of Fenix Marine Services rail terminal on June 8, 2023, taken by a trucker.

The “slow and go” pace of the International Longshore and Warehouse Union workforce at West Coast ports has slowed ground port productivity to a crawl. As a result, supply chain intelligence company MarineTraffic data shows what it is calling a “significant surge” in the average number of containers waiting outside of port limits.

At the Port of Oakland, during the week of June 5, the average TEUs (ton equivalent units) waiting off port limits rose to 35,153 from 25,266, according to MarineTraffic. At the Port of Los Angeles and Long Beach, California, the average TEUs waiting off port limits rose to 51,228 from 21,297 the previous week, said a MarineTraffic spokeswoman.

The value of the combined 86,381 containers floating off the ports of Oakland, Los Angeles, and Long Beach reached $5.2 billion, based on a $61,000 value per container, and customs data.

According to data exclusively pulled for CNBC by Vizion, which tracks container shipments, the seven-day rate for a container cleared through the Port of Oakland is operating at 58%; at Port of Long Beach it is 64%; and at Port of Los Angeles it is 62%.

“Our data shows that vessels will continue arriving at West Coast ports in the coming days with significant amounts of cargo to unload,” said Kyle Henderson, CEO of Vizion. There are no indications at this time that ocean carriers have plans to cancel any sailings to these ports, he said, but he added, “If these labor disputes continue to affect port efficiency, we could see backlogs similar to those experienced during the pandemic. Obviously, that’s the last thing that any shipper wants as we turn the corner into the back half of the year and peak season.”

Logistics managers with knowledge of the way the union rank-and-file displeased with unresolved issues in negotiations with port management are influencing work shifts tell CNBC the slowdown can be attributed to skilled labor not showing up for work. CNBC has also learned that at select port terminals, requests for additional work made through official work orders are not being placed on the wall of the union hall for fulfillment. The Pacific Maritime Association, which negotiates on behalf of the ports, is not allowed in the union hall to see if the terminal orders are indeed being requested. CNBC has been told that if the additional job postings were being put up the data would show they are not being filled. Only original labor ordered from the PMA is being filled.

The PMA said in a statement on Friday afternoon that between June 2 and June 7, the ILWU at the Ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach refused to dispatch lashers who secure cargo for trans-Pacific voyages and unfasten cargo after ships arrive. “Without this vital function, ships sit idle and cannot be loaded or unloaded, leaving American exports sitting at the docks unable to reach their destination,” the statement read. “The ILWU’s refusal to dispatch lashers had been part of a broader effort to withhold necessary labor from the docks.”

PMA cited a failure on Wednesday morning to fill 260 of the 900 jobs ordered at the Ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach, and in total, 559 registered longshore workers who came to the dispatch hall were denied work opportunities by the union, PMA asserted in its statement.

“Each shift without lashers working resulted in more ships sitting idle, occupying berths and causing a backup of incoming vessels,” it stated.

However, the PMA said ILWU’s decision to stop withholding labor has allowed terminals at the Ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach to avert, for now, “the domino effect that would have resulted in backups not seen since last year’s supply chain meltdown.”

The PMA cited “generally improved” operations at the Ports of Los Angeles, Long Beach, and Oakland, but at the Ports of Seattle and Tacoma, a continuation of “significant slowdowns.”

The ILWU has declined to comment, citing a media blackout during ongoing labor talks.

Truck and container backups

The average truck turns to go in and out of the West Coast ports are up.

A trucker waiting for a container at LA’s Fenix Marine Services terminal shared photos from their truck with CNBC showing congestion on both rail and the road where truckers wait to pick up their containers.

Shippers are becoming increasingly concerned about the potential need to find alternative supply chain options.

A spokesperson for Long Beach, California-based Cargomatic, which focuses on drayage and short-haul trucking logistics, said it isn’t yet seeing trade diversions, but added, “As a national drayage partner, we have contingency plans built in with capacity ready to service our customers anywhere in the U.S. We know that shippers are very nervous and it’s only a matter of time before they pivot if this situation becomes prolonged.”

The PMA said in its statement that even though some port operations have improved, “the ILWU’s repeated disruptive work actions at strategic ports along the West Coast are increasingly causing companies to divert cargo to more customer-friendly and reliable locations along the Gulf and East Coasts.”

West Coast ports, which had lost significant volume to East Coast ports over the past year due to volatility in the labor contract talks, had in recent months begun to gain back volume.

A photo of a truck build up at Fenix Marine Services terminal at the Port of Los Angeles waiting to pick up containers taken by a trucker.

Ocean freight intelligence company Xeneta says its data shows that container spot freight rates jumped 15% in the first days of June as a result of several simultaneous disruptions. Recent Panama Canal low water levels limited cargo throughput, and soon after that, large parts of U.S. West Coast ports stopped handling inbound and outbound container trade.

“Shippers in search of more reliable and resilient supply chains now consider their options,” said Peter Sand, chief analyst at Xeneta. “The longer this drags on, the more severe the consequences will be for shippers and terminals,” he said.

During Covid, the supply chain breakdowns saw the pileup of vessels waiting off the West Coast influence trade to move to the Gulf and East Coast Ports. If vessels do start diverting again, there are extra costs tacked onto the goods being transferred, which the shipper will be charged. If the vessels divert and go to the Gulf or East Coast ports, they have to either use the Panama Canal, where extra charges on top of the normal additional charges are levied because the Panama Canal is in a critical situation with lower water levels due to drought.

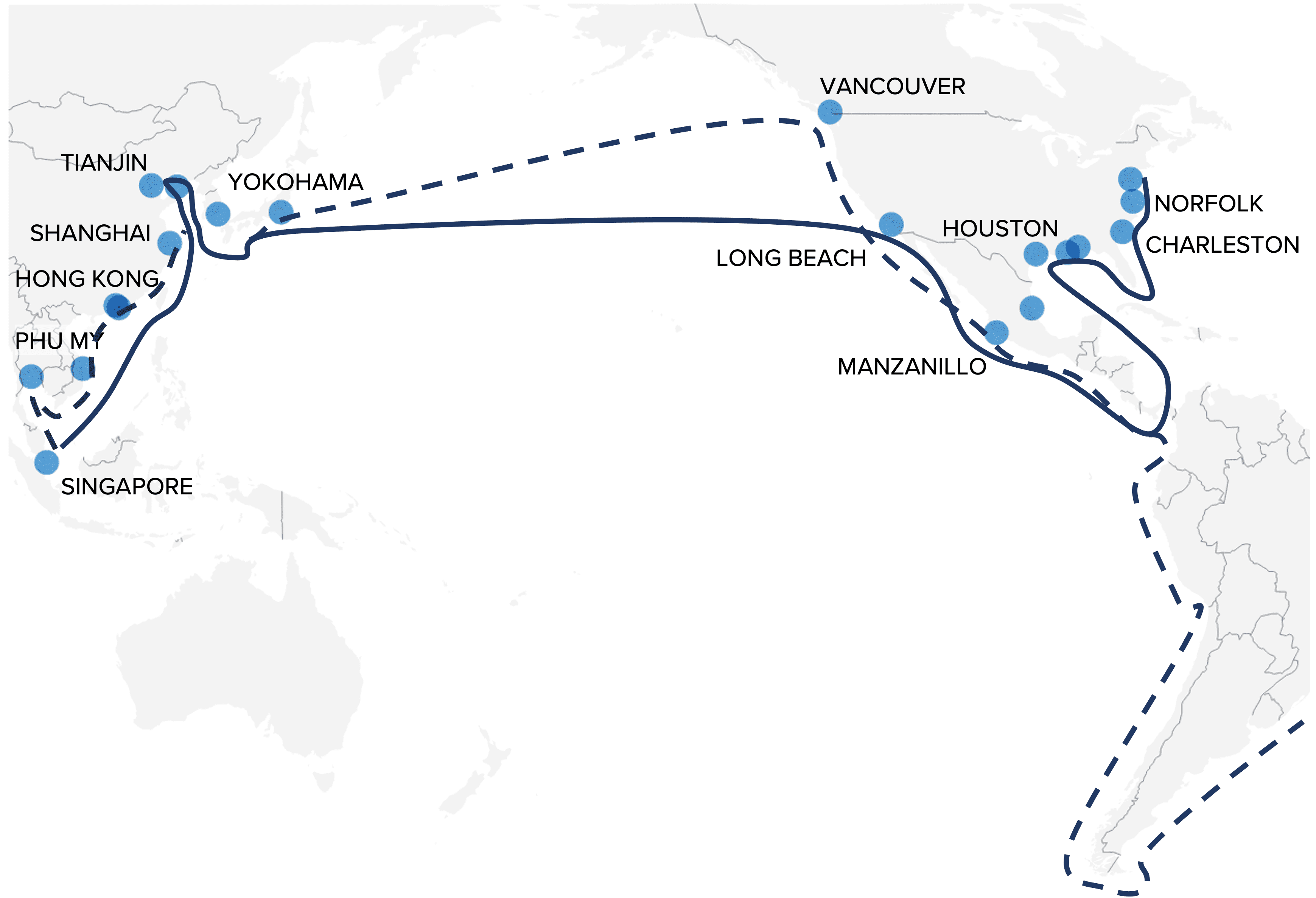

Routes for monthly long-term ‘tramp sailings’ from Asia to the Americas

— Core trade route — Alternate route

The Panama Canal’s water issues exacerbate costs that would be incurred in any trade re-routing. It has instituted weight requirements for vessels — they need to be lighter to move through. If the vessel is at or under that weight requirement, shippers will be paying additional charges. In addition to the canal fees, some ocean carriers like Hapag Lloyd have instituted a $260 container fee for traveling through the canal. CMA CGM is charging $300 a container. If vessels are heavier than the current requirement, they would be forced to traverse the Pacific Ocean and go around the horn of South America, which would add weeks of travel time and travel costs.

“Vessel diversions are some of the most difficult activities that shippers and our clients deal with during a crisis,” said Paul Brashier, vice president of drayage and intermodal at ITS Logistics. During the pandemic and its aftermath, containers destined for Los Angeles or Long Beach would show up unannounced in Houston or Savannah with little to no notice, he said. “We have visibility applications that alert us prior to the container arriving so we can reassign trucking capacity at the new port. But if you don’t have this visibility, if you are not able to track the containers like that in real time, you could face thousands of dollars more in shipping and D&D costs per container to accommodate those changes. That inflationary pressure adversely not only affects the shipper but the consumer of those goods,” he added.

ITS Logistics raised its freight rail alert level to “red” this week, signifying severe risk.

Supply chain costs have come down considerably on a global basis, according to the Federal Reserve’s data, though they have been mentioned by Fed Chair Jerome Powell as one inflationary trigger the central bank has no control over. In a report by Georgetown economist Jonathan Ostry, the spike in shipping costs increased inflation by more than two percentage points in 2022.

“These slowdowns leave little options for shippers who have containers already en route to the West Coast,” said Adil Ashiq, head of North America for MarineTraffic, who told CNBC earlier this week that the maritime supply chain issues were “breaking normal.”

“They could skip a port and go to another West Coast port, but they are all experiencing levels of congestion,” he said on Friday. “So do they wait or divert and go to Houston as the next closest port to discharge cargo?”

If vessels do decide to reroute, it will add days to their journey, which would delay the arrival of the product even more.

For example, if a vessel inbound from Asia decided to reroute to Houston, it would add another 7 to 11 day journey to the Panama Canal. If a vessel is approved to transit through the canal, that adds 8-10 hours of transit time. “You then have to add travel time once out of the canal to the port. So we’re looking at conservatively, a 12 to 18 day additional delay if a vessel decides to go to Houston directly from the Canal. Even more, if you have to travel around South America,” he said.

Key sectors of the U.S. economy have been pleading with the Biden administration to step in and broker a labor agreement, including trade groups for the retail and manufacturing sectors. On Friday, the U.S. Chamber of Commerce added its voice to this effort, expressing its concerns about a “serious work stoppage” at the ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach which would likely cost the U.S. economy nearly half a billion dollars a day. It estimates a more widespread strike along the West Coast could cost approximately $1 billion per day.

“The best outcome is an agreement reached voluntarily by the negotiating parties. But we are concerned the current sticking point – an impasse over wages and benefits – will not be resolved,” U.S. Chamber of Commerce CEO Suzanne Clark wrote in a letter to President Biden.

![Lukas Graham – 7 Years [Official Music Video] Lukas Graham – 7 Years [Official Music Video]](https://i.ytimg.com/vi/LHCob76kigA/hqdefault.jpg)