HONG KONG — A Hong Kong court on Thursday found 14 of 16 pro-democracy activists guilty of conspiring to subvert the state in the Chinese territory’s single largest case under a sweeping national security law imposed by Beijing.

Two of the defendants, Lau Wai-chung and Lee Yue-shun, were found not guilty.

The defendants, who could be sentenced to life in prison, are among 47 politicians, academics and other pro-democracy figures who were charged with conspiracy to commit subversion over their involvement in an unofficial primary election. The judgment is being issued by Hong Kong’s High Court over two days on Thursday and Friday.

Critics say the trial symbolizes the decline of freedoms in the international financial hub amid a crackdown on dissent following mass anti-government protests in 2019.

“This trial is not just a trial for these 47 individuals,” said Eric Yan-ho Lai, a research fellow at the Georgetown Center for Asian Law. “It’s a trial for the pro-democracy movement in Hong Kong.”

Most of the 47 have been held without bail since being charged in early 2021. Of those, 31 pleaded guilty in the hopes of a reduced sentence, while the remaining 16 pleaded not guilty.

The 47 range in age from their 20s to their 60s and include prominent names such as legal scholar Benny Tai, former pro-democracy lawmaker Claudia Mo and Joshua Wong, best known internationally as a leader of pro-democracy protests in 2014. The defendants who pleaded not guilty and were convicted on Thursday include former lawmakers Leung Kwok-hung and Raymond Chan and journalist-turned-activist Gwyneth Ho. They went on trial in February 2023 and had been waiting for a ruling since it ended in December.

Hong Kong had had a 100% conviction rate in national security cases, which are prosecuted under rules that diverge from the city’s legal norms, including presumption against bail. Almost 300 people have been arrested under the national security law, which came into force in the summer of 2020.

The charges stem from an informal primary election held in July 2020 in which more than 600,000 voters selected pro-democracy candidates for a legislative election that was scheduled for that September. Many of the candidates in the primary election had vowed to repeatedly veto the government’s proposed budget in an effort to force the resignation of Carrie Lam, who was then the city’s leader and seen as resistant to the 2019 protesters’ democratic demands.

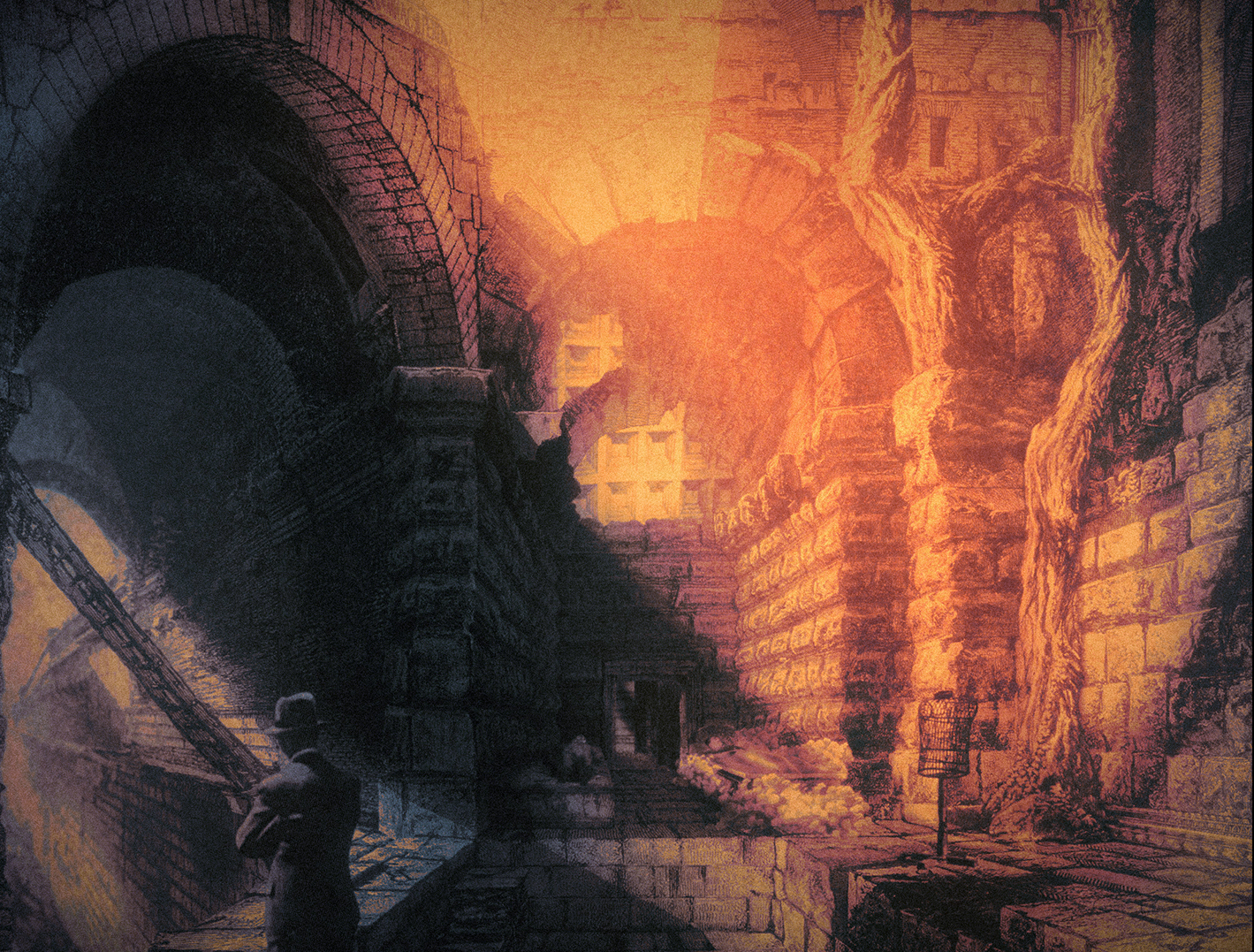

People queue outside the West Kowloon Magistrates’ Court in Hong Kong on May 30, 2024 as it convenes to deliver verdicts in the city’s biggest case against pro-democracy campaigners since China imposed a national security law to crush dissent.

Peter Parks | Afp | Getty Images

Officials warned at the time that the election might violate the national security law that Beijing had imposed less than two weeks earlier in response to the 2019 protests, which roiled Hong Kong for months and sometimes turned violent.

Hong Kong and Chinese officials said the law, which criminalized secession, subversion, terrorism and collusion with foreign forces, was necessary to restore stability. But critics say it has driven a broad crackdown on dissent in Hong Kong, a former British colony that was promised its Western-style liberties would be preserved for 50 years upon its return to Chinese rule in 1997.

In January 2021, more than 50 activists were arrested in connection with the unofficial primary, 47 of whom were later charged. The legislative election, which officials had postponed citing the pandemic, was held in December 2021 after election laws were overhauled to ensure that only “patriots” could run for office.During the trial, prosecutors argued that the defendants were trying to paralyze the Hong Kong government by agreeing to indiscriminately veto government budgets. They noted that Tai, a main organizer of the primary, had said pro-democracy lawmakers could use a majority in the legislature as a “constitutional weapon.”

The defendants’ lawyers argued that the maneuver their clients planned to use was constitutional and that the means of subverting state power could not be “unlawful” unless they involved physical violence or criminal conduct.

Those who pleaded guilty, including four who testified for the prosecution, may have been hoping for sentence reductions of up to one-third. They will be sentenced later.

The 14 defendants who pleaded not guilty and were convicted on Thursday will also have the opportunity to ask for more lenient sentences at later hearings.

Some, such as Wong, have already been sentenced to prison after being charged in multiple other cases related to the 2019 protests or banned memorials for victims of the 1989 Tiananmen Square crackdown.

Even those who are not serving other sentences have mostly spent more than three years in detention, missing out on years with their families amid repeated delays in their trial. One of them, Wu Chi-wai, a former leader of the Democratic Party, has lost both his parents since he was detained.

Lai, who co-wrote a report on the national security crackdown published in March, said the Hong Kong 47 trial shows that “separation of powers or judicial independence are no longer as autonomous as before.””The national security agenda is expanding to all areas of rule of law in Hong Kong now,” he said, pointing to the city’s recent ban on the 2019 protest anthem “Glory to Hong Kong.” “It’s not just about the criminal courts.”

The Hong Kong government says the city continues to have rule of law, citing last year’s Rule of Law Index by the World Justice Project in which Hong Kong ranked 23rd out of 142 countries and regions, three spots higher than the United States.

In March, Hong Kong’s opposition-free legislature unanimously approved the city’s own national security law, known locally as Article 23. The first arrests under that law, of six people accused of publishing seditious social media posts, were announced on Tuesday.

![Mason Ramsey – Twang [Official Music Video] Mason Ramsey – Twang [Official Music Video]](https://i.ytimg.com/vi/xwe8F_AhLY0/maxresdefault.jpg)

![Young Colton, Del and Evelyn in 1974 [VIDEO] Young Colton, Del and Evelyn in 1974 [VIDEO]](https://tvline.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/01/the-way-home-season-3.jpg?w=650)