Every movie is different; different stories, different actors, different characters, different languages, different genres. The great constant in all of them is time. The time it takes to make them. The time it takes to watch them. It is the uniting factor in every single film, as it is in all of our lives.

Onscreen characters can sometimes travel through time or stop it entirely, and the creators of movies can use editing to alter the flow of time. But for the audience in the theater, the clock never stops ticking. That’s one of the concepts bubbling through The Clock a one-of-a-kind, 24-hour video essay.

Director Christian Marclay (plus a team of researchers) compiled thousands of film clips involving clocks, watches, and references to specific times of day, then edited them together into a chronological loop that also functions as a working clock. Whatever time it is when you watch The Clock, that’s the time it is onscreen.

Marclay developed The Clock over a period of five years and first showed it publicly in 2010. It’s currently on display at MoMA — but only during the museum’s operating hours. (They held one 24-hour screening of the whole thing back in December. It sold out instantly.)

I missed The Clock the handful of times it’s played in New York City in the past, so I was determined to catch it this time. The screening room where it’s on display in MoMA isn’t large, and contains just three rows of cramped Ikea couches. Once the room reaches capacity, you have to join a virtual queue and wait for someone inside to leave before you get your turn. Once you’re inside, you can watch as long as you want. But if you have to get up for a bathroom or food break, you’ve got to wait on line again if you want to go back in. Hoping to avoid a significant wait time, I showed up at MoMA right they opened at 10:30 AM. Thankfully, I was able to walk right in.

A film compiled entirely from snippets of movie scenes involving the passage of time might sound boring or repetitive. (The woman who sat down next to me turned to her companion and whispered “Wait, this is it?” when the reality of what she’d signed up for fully dawned on her.) In fact, the 100 minutes I spent watching The Clock passed faster than any others I’ve spent in 40+ years of going to the movies (or to big black rooms filled with Ikea furniture). I couldn’t believe how quickly 10:30 turned into 12 PM. If I didn’t have a job and responsibilities I would have sat there until MoMA kicked me out. (If MoMA didn’t kick people out when they closed, I would have gladly sat there for 24 hours.) Paradoxically, it seems that calling attention to the passage of time in a cinematic context only makes it move faster.

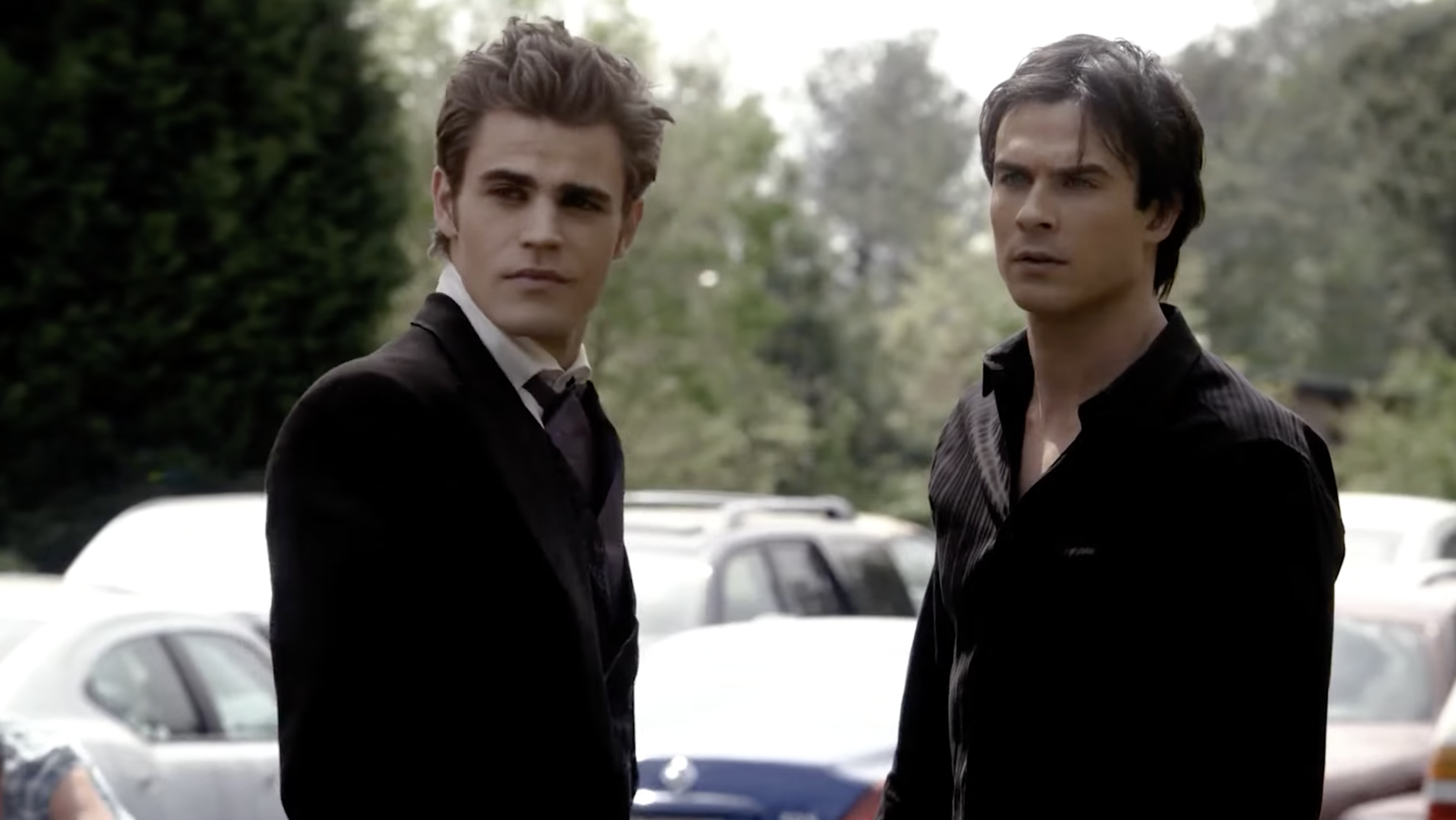

Certainly The Clock contains its share of superficial pleasures. It’s fun when you instantly recognize a movie.(Some of the films that appeared in the excerpt I watched: The Breakfast Club, Once Upon a Time in the West, Big Daddy, The 400 Blows, The Bank Job, The Game, Sideways, Falling Down, The Quick and the Dead, High Noon, Bad Santa, Easy Rider, and Dressed to Kill.) I also spotted a clip from one television show, which felt a little bit like a betrayal of Marclay’s pact with his audience. Then again, given that the clip in question was from the episode of The Twilight Zone entitled “Time Enough at Last,” perhaps its thematic link to The Clock’s central conceit was strong enough to merit its inclusion.

It’s also fun when you don’t recognize Marclay’s film picks, which happens quite often in a video essay comprised of some 12,000 movie excerpts. A viewing of The Clock is sure to inspire a viewer to go track down (or at least Google) some of the stranger scenes. As soon as I left the theater, I looked up the sequence in which a man climbs out onto the face of Big Ben to delay a bomb explosion. (It’s from the 1978 remake of The Thirty Nine Steps, directed by Don Sharp.) Even stripped of context, that sequence was suspenseful; watching a man dangle hundreds of feet in the air will always make your palms sweat, even if you don’t know who the man is or why he’s up there. Funny how that — and all movies — work, something you get plenty of time to contemplate watching The Clock.

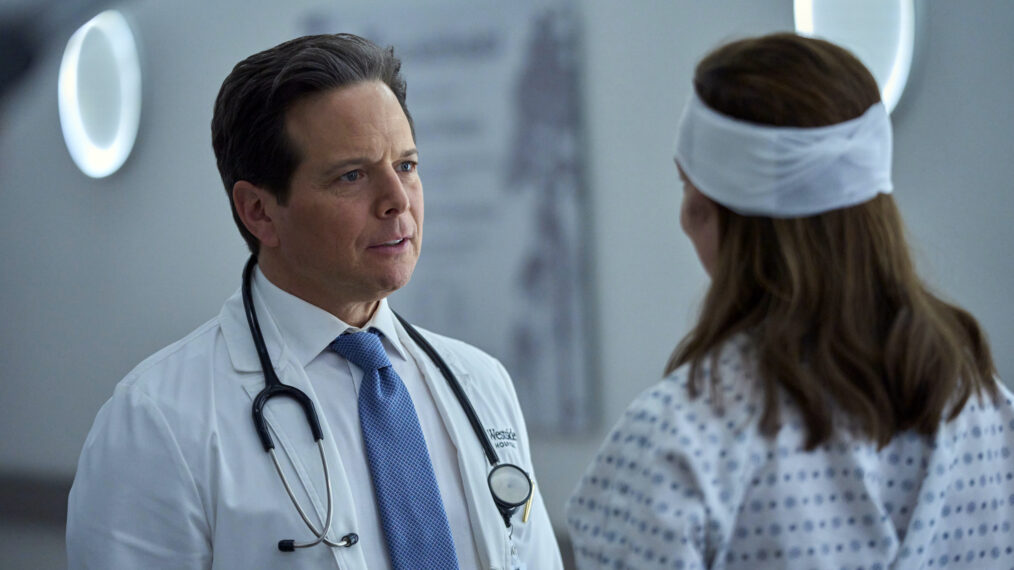

But there’s a lot more to The Clock than that. Its structure calls attention to how time works, both on and off screen; how so many thrillers use a literal ticking clock as a storytelling crutch, and how so many others use it to enhance a punchline. Maclay includes a ton of scenes that feature recognizable actors, whose presence has a stabilizing effect on our attention. (A familiar face in a movie instantly aligns us with that character even if, as in the case of The Clock, their actions and motivations are unclear.)

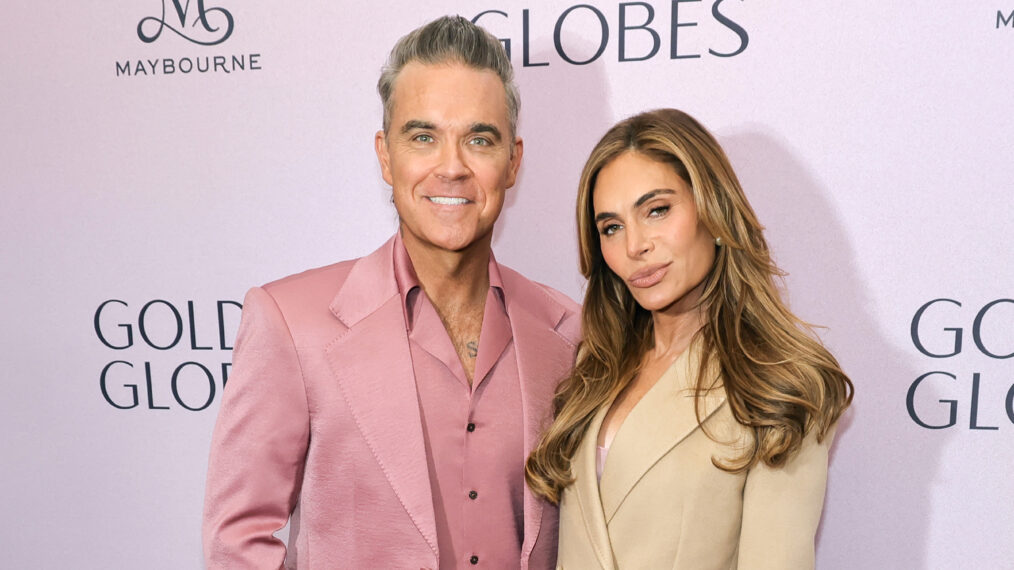

Recurring cameos from famous movie stars also allow the viewer to contemplate the effect of the passage of time on the human body. In the feature-length segment I saw this week, Charles Bronson popped up three different times at three totally different ages; once as a young hunk, once as a weathered, confident star, and once as a fading action hero. Photography captures a moment in time, but if you string enough of those moments together you start to see time flow and ebb and slip through the proverbial hourglass.

Sadly, I could only stay for 100 minutes of The Clock before I had to surrender my seat to another willing participant in this illuminating and slightly hypnotic experiment. As I got up to exit the theater, the film shifted to a horrible traffic accident from a movie I didn’t recognize. Then suddenly Humphrey Bogart was onscreen; continuity editing gave the illusion that he had looked out the window in his film to spy that car accident somehow.

Whatever happened next, I don’t know. I left, and The Clock kept going. Time marches on.

The Clock is on view at the Museum of Modern Art in New York City through February 17.

The Dumbest Questions People Ask Google About Movies

These are all real questions from the “People Also Ask” section of Google. People asked these questions!

![Iggy Azalea – Money Come [Official Music Video] Iggy Azalea – Money Come [Official Music Video]](https://i.ytimg.com/vi/7t5V5ygeqLY/maxresdefault.jpg)